Science and the Environment

Posted by John Baez

As the year’s end approaches and I hole up at home, free of the pressures of teaching, my thoughts roam a bit more freely. So, they naturally turn to questions like this: am I doing the right things?

For example: should I do more to help save the planet? And if so, how can I do it in a way that takes advantage of my special skills? An education in math and physics leads people to value simple, elegant problems. The ecological crisis we face is anything but: it’s an incredible mess. Is there anything a mathematical physicist can do to help that a biologist or politician can’t do better? I try to proselytize on my webpage, but is that enough?

Questions like this don’t fit comfortably into this blog. So, I apologize to readers who prefer the usual fare. But these questions seem too important to completely ignore — and they’re especially timely for this reason:

In just a few weeks, science policy in the US may be run by scientists.

Here’s what’s happening:

Barack Obama appointed Nobel laureate physicist Steven Chu as head of the Department of Energy. On May 9, 2007, Chu said "If I were emperor, I would put the pedal to the floor on energy efficiency and conservation." As director of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Chu pushed scientists to develop technologies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Obama appointed MacArthur prizewinner and Woods Hole director John Holdren to be his science advisor. Holdren recently compared our current approach to climate change to:

being in a car with bad brakes driving towards a cliff in the fog.

In the October issue of Scientific American, Holdren wrote:

Unfortunately, the Bush administration has wasted the last eight years. It should have been taking decisive action but engaged instead in systematic understatement of the danger: it has made ridiculous assertions that the U.S. should not do anything that China does not agree to do and has stubbornly insisted that no action should be taken to improve climate change ‘if it hurts the economy.’ This last rationalization translates into ‘if it costs anybody any money’ and is roughly akin to saying that the country should not defend itself against terrorism because that costs money.

He recently gave this speech at Harvard:

- John Holdren, Global Climate Disruption: What Do We Know? What Should We Do?, speech at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, November 6, 2007.

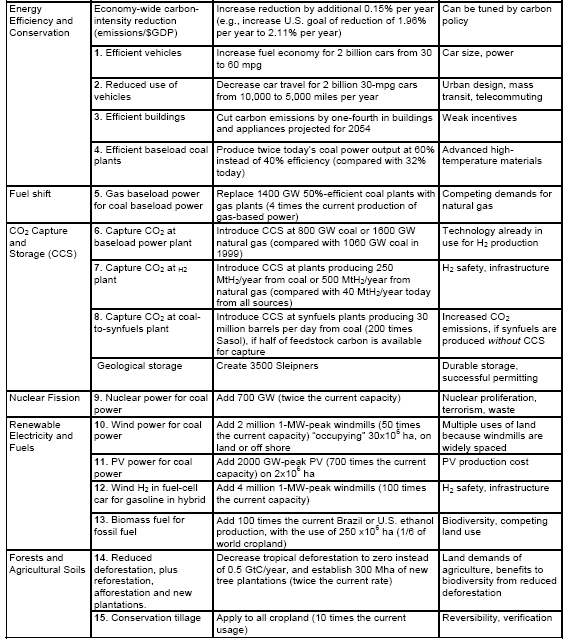

He begins by explaining the problem and its causes. Then, starting on page 30 of the PDF file of his speech, he describes what we can realistically do. The short answer: there’s no panacea; we need to pursue many strategies. But the "cheapest, fastest, cleanest, surest source of emissions reductions is to increase the efficiency of energy use in buildings, industry and transport."

Obama has also appointed the MacArthur prize-winning zoology professor Jane Lubchenco to head NOAA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which does most of the US government research on climate change, and regulates fisheries.

Lubchenco recently gave this speech:

- Jane Lubchenco, Advocates for Science: The Role of Academic Environmental Scientists, speech at the conference The Scientist as Educator and Public Citizen: Linus Pauling and His Era, Oregon State University, October 29-30, 2007.

She says that her research in oceanography started out being fun, and intellectually challenging:

I received my PhD from Harvard in 1975, and was steeped in the culture of the ivory tower. My mentors, at Harvard, the University of Washington, and a research group that I spent a lot of time with at the University of California at Santa Barbara, were collectively the most stellar ecologists in the field. I have just a really impeccable pedigree if you want to count those kinds of things. My mentors were very much focused on doing your science, publishing in the scientific literature, getting grants, and pushing the intellectual frontiers of the discipline. That was what we did. It was exciting, it was fun, it was tremendously challenging, and it was very, very rewarding. I think this is fairly typical of a lot of scientists of my generation.

But then things started to change:

Over time, many, many ecologists observed that the systems they were studying were changing before their very eyes. Ecologists that would go back to the same places year after year after year started seeing changes that had not been documented before. The changes were different, they were happening faster, and many more ecologists began to take note of "how is it changing," and "why is it changing," not just "how does it work?" The next sort of step in that process was "what are the consequences of these changes," not just to the ecosystems but to the people who depend on them, and finally, "how can we do a better job of managing activities that are causing the changes, or of mitigating the changes that are underway?" And so, over the thirty years that I’ve been a practicing scientist, there has been a real revolution in the nature of the questions that ecologists have been asking of the world, driven in part by larger-scale changes that they were observing.

As part of this revolution, she helped propose Sustainable Biosphere Initiative. I hope that at NOAA she can start to implement some of these ideas. The oceans, in particular, are under a double assault by climate change and overfishing. She writes:

Fisheries peaked in the mid 80’s and have been on the decline since then. This represents, in part, the sequential depletion of one fishery after another, after another. We also have data suggesting that 90% of all the big fish of the ocean are gone. The huge tuna, sharks, swordfish, marlin, and other icons of the sea have been very significantly depleted primarily by industrial-scale fishing over the last couple of decades.

There are major changes underway in oceans. In addition to that, more and more ocean ecosystems are undergoing very rapid, abrupt change. They are complex, nonlinear systems that are characterized by tipping-points, and we’re seeing very rapid changes, loss of resilience in these systems, loss of ability to cope with changes, and in fact very radical change as a result.

When I read things like this, I wonder what I should be doing. I’m sure many of you have faced these questions too.

Re: Science and the Environment

Scientists have to lift the fog. It’s for others to build the brakes and apply them. We need a Ministry/Department of Truth, not to generate spin (as in “1984”), but to oppose it by conducting open vigorous well-funded mathematically literate investigations of the facts, backed by substantial powers of investigation and cross examination. Our responses to the looming energy crisis have been: The Hydrogen Economy, Biofuels and the Iraq war. The last is out of scope, but the first two wouldn’t have survived vigorous investigation. We’re down to our last few rolls of the dice on this. I urge everybody to see what can be done without the “well funded” bit, by looking at Sustainable Energy — Without the Hot Air, written by Prof David MacKay, head of the Inference Group in the Physics dept at Cambridge Uni. Yes we badly need well respected mathematically literate people to lead our society in thinking clearly about what will and won’t work.