Should Mathematicians Cooperate with GCHQ? Part 3

Posted by Tom Leinster

Update (6 July 2014) A much shorter version of this post appears in the July edition of the LMS newsletter, along with a further opinion from Trevor Jarvis (Hull).

In April, the newsletter of the London Mathematical Society published my piece “Should mathematicians cooperate with GCHQ?”, which mostly consisted of factual statements based on the Snowden leaks, followed by the mild opinion that as individuals and institutions, we can choose whether to give GCHQ our cooperation. Two mathematicians associated with GCHQ, Richard Pinch and Malcolm MacCallum, have now replied. I will address their points, then make some suggestions for mathematics departments in the post-Snowden era.

Real, not-made-up

logo of US spy satellite

Neither Pinch nor MacCallum disputes any individual factual statement that I made. (In both my earlier article and this one, every factual statement is hyperlinked to supporting evidence.) Neither seriously engages with the fact that the intelligence agencies are collecting not just terrorists’ communications, but everyone’s — by its own account, GCHQ intercepts over 50 billion communication events every day. Neither justifies the total surveillance philosophy pithily described by GCHQ’s closest partner, the US National Security Agency:

Collect it all. Sniff it all. Process it all. Know it all. Partner it all. Exploit it all.

In response to all this, Pinch and MacCallum say, effectively: “Trust us.”

Fortunately, no one needs to trust them, or me, because we now have plentiful documentary evidence of what GCHQ and its partners are doing. So we can simply test claims against the evidence.

For example, on the one hand, Pinch quotes GCHQ director Iain Lobban’s claim that if his staff “were asked to snoop, I would not have the workforce. They would leave the building.” On the other, GCHQ’s own documents detail how it surreptitiously harvested webcam images from millions of ordinary people suspected of no crime, using a system that “does not select but simply collects in bulk.” The documents note how many of the secretly captured images are sexually explicit. If that is not “snooping”, what is?

Although neither Pinch nor MacCallum disputes any factual statement that I made, MacCallum does dispute one I didn’t make, writing: “Both GCHQ and its mathematics staff will be amused by the accusation that mathematicians there have little idea how their work will be used.” In fact, I said “mathematicians working for GCHQ may have little idea …”, and I stand by that: first, for the reason that MacCallum immediately concedes — that information-sharing within GCHQ is limited by “need to know” — and second, based on conversations with mathematicians who have worked for GCHQ over sabbaticals or summers. Some of those mathematicians now regret ever having been involved, having had no idea that they were working for an agency of mass surveillance.

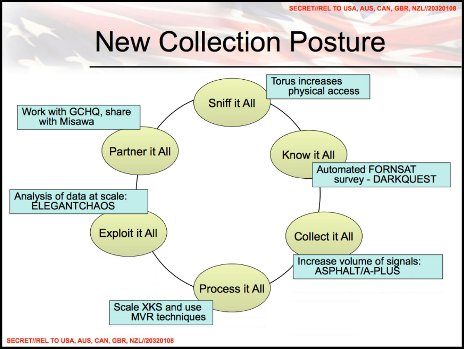

Slide

from NSA presentation to GCHQ and other partners, 2011

We all want spies to spy on known or suspected terrorists. We all agree that the secret services must have secrets. We all support targeted surveillance, under careful legal constraints. But what is at issue here is mass surveillance: the monitoring of everyone, all the time.

Pinch and MacCallum blur that distinction. Thus, MacCallum cites the claim of MI5 head Andrew Parker that the intelligence agencies and police have disrupted many “plots towards terrorism”. But Parker did not say this was due to any mass surveillance programme; on the contrary, he added that almost all the plots came from a known pool of several thousand individuals. Even more tangentially, MacCallum notes the usefulness of phone billing records in criminal trials; but these are obtained from phone companies, not state surveillance of any kind.

MacCallum accuses me of making “multiple contentious statements”, but is careless with the facts himself. As well as mischaracterizing what I wrote about mathematicians working for GCHQ, he is inaccurate when reporting Andrew Parker’s claim about disrupted plots. What Parker actually said was that since July 2005:

I think … there have been 34 plots towards terrorism that have been disrupted in this country, at all sizes and stages. … Of that 34, most of them, the vast majority, have been disrupted by active detection and intervention by the Agencies and the police. One or two of them, a small number, have failed because they just failed. The plans did not come together.

MacCallum renders this as:

I was pleased to hear, in the public session Richard Pinch’s response refers to, that 34 terrorist plots had been thwarted in recent years by the intelligence agencies.

This is inaccurate in at least three respects. First, Parker’s words were “Agencies and the police”, not “intelligence agencies”. Perhaps many plots were disrupted by the police alone. Second, MacCallum forgets to subtract from the 34 the plots that failed of their own accord. Third and most importantly, Parker used the vague form of words “plots towards terrorism”, not “terrorist plots”. It is far from clear what he intended this phrase to encompass (“towards”?), especially in a country where the looseness of the legal definition of terrorism has been a longstanding source of concern, and where anti-terrorism laws have been used to prevent everything from photographing the police to peaceful protest to heckling. Whether the true figure is 3 or 300 makes little difference to the argument, since the disruptions were not claimed to be due to mass surveillance anyway. But when MacCallum is so careless with simple, easily verifiable facts, why should we trust those of his claims that are unverifiable?

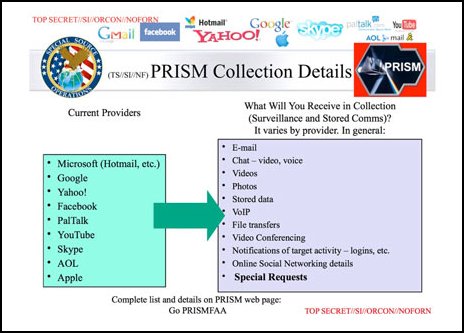

Slide on the PRISM programme, outlining how the largest internet

companies provide their users’ data to the NSA

If mass surveillance was known to be an effective tool for preventing terrorism, we could debate whether it was a price worth paying. But the intelligence agencies have been unable to point to success stories so far. In a US court ruling, federal judge Richard Leon noted the “utter lack of evidence that a terrorist attack has been prevented” by the NSA’s bulk data collection (despite the government having been able to submit classified evidence to him). And a CIA report on 9/11 concluded that the agencies had enough information to prevent the attacks, but failed to use it effectively.

At the heart of this discussion is trust. Through systematically monitoring our phone calls, emails, web browsing, location, and so on, the world’s most powerful intelligence agencies hold intimate personal information on much of the population. They have almost limitless power to spy on us. Do we trust them to use that power responsibly?

GCHQ insiders such as MacCallum and Pinch presumably do. They might say that the agencies work hard to prevent terrorism, and are not interested in the mundane details of your life. But between those extremes, there is a large grey area — the area where activism, protest and civil disobedience lie, the area where powers are most likely to be abused.

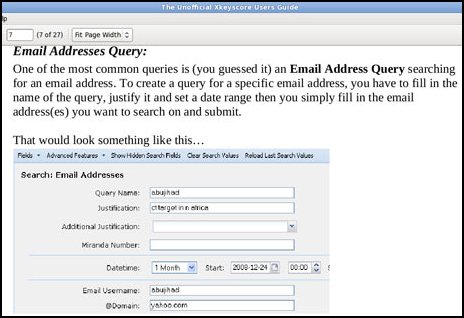

There is strong evidence that when surveillance powers are exercised in secret, abuse is inevitable: from the FBI recording Martin Luther King’s extramarital affairs and attempting to incite him to suicide over it, to present-day GCHQ undermining the online activism of people not suspected of any crime, to the NSA gathering the pornographic web-browsing habits of Muslims who it explicitly notes are not terrorists. Via GCHQ and NSA bulk collection programmes, agency analysts can access almost anyone’s email. Inevitably, this power has been abused too, with analysts exploiting it to read the mail of their own ex-partners and even Bill Clinton.

Page from NSA guide to the XKeyScore programme, showing staff how

to read an arbitrary person’s email

Perhaps the secret services could be restrained from abusing their powers if there were a really strong external body enforcing strict rules. Insiders such as Pinch and MacCallum may perceive the existing oversight of GCHQ as strict, but few outsiders do. For example, the GCHQ oversight system was recently excoriated by a parliamentary committee as “not fit for purpose” and “embarrassing”. Even GCHQ’s own documents show it using its lax oversight as a selling point to the NSA. According to a senior GCHQ lawyer, “we have a light oversight regime compared with the US” — where for context, the NSA is regulated by a secret court at which only the agencies’ side of the case is represented, without opposition, and which rejects just 1 in 3000 of the NSA’s surveillance requests.

Neither MacCallum nor Pinch addresses anything we have learned from the Snowden documents; they appear to be forbidden to join the conversation that the rest of the world is having. GCHQ routinely refuses to discuss matters of clear public interest that have been all over the news for the last year. Even the NSA is more open, being obliged to submit to genuine adversarial questioning at senate hearings. For instance, it was at one such hearing that the NSA chief conceded that the number of terrorist plots thwarted by bulk surveillance was not 54, as repeatedly claimed, but at most one or two (his best example being a man found giving an alleged terrorist group $8500). On both sides of the Atlantic, senior politicians on national security committees have complained that they were never even informed of the existence of the mass surveillance programmes, let alone authorizing them. We are not in democratic control.

Heads of mathematics departments would probably like to “stay out of politics”. This is wishing for the impossible. It is illogical to maintain that dissenting from cooperation with GCHQ is a political act, but assenting is not. A head of department who runs a working relationship with GCHQ is engaged in a political act just as surely as one who declines.

The very least HoDs can do is to consult openly with their departments. The risks of not doing so have recently been illustrated in London, where Imperial, King’s and UCL have set up joint postdoctoral positions with GCHQ’s Heilbronn Institute. In at least one case, this was done without consulting the department about the ethical implications, causing later resentment and anger. GCHQ may want to normalize the presence of its employees within the academic community, but not all of our community accepts this. It is no longer realistic for HoDs to treat GCHQ as if it was just another partner. Schools of medicine and psychology must routinely assess the ethical risks of their work. Perhaps it is time for mathematics departments to draw up their own ethical policies.

Mathematicians have always had to navigate difficult ethical territory, from ancient military applications to the role of quants in the banking crash. But now that we have detailed documentary evidence of what kind of activities we are supporting when we collaborate with the secret services, we can use it to have a properly evidence-based discussion. Instead of seeking refuge in the comforting myth of political neutrality, we should take responsibility for our actions.

Re: Should Mathematicians Cooperate with GCHQ? Part 3

now AG Holder wants to focus on ‘domestic terrorists’. Maybe they wanted to go there since they started this.