Lattice Paths and Continued Fractions I

Posted by Simon Willerton

In my last post I talked about certain types of lattice paths with weightings on them and formulas for the weighted count of the paths, in particular I was interested in expressing the reverse Bessel polynomials as a certain weighted count of Schröder paths. I alluded to some connection with continued fractions and it is this connection that I want to explain here and in my next post.

In this post I want to prove Flajolet’s Fundamental Lemma. Alan Sokal calls this Flajolet’s Master Theorem, but Viennot takes the stance that it deserves the high accolade of being described as a ‘Fundamental Lemma’, citing Aigner and Ziegler in Proofs from THE BOOK:

“The essence of mathematics is proving theorems – and so, that is what mathematicians do: They prove theorems. But to tell the truth, what they really want to prove, once in their lifetime, is a Lemma, like the one by Fatou in analysis, the Lemma of Gauss in number theory, or the Burnside-Frobenius Lemma in combinatorics.

“Now what makes a mathematical statement a true Lemma? First, it should be applicable to a wide variety of instances, even seemingly unrelated problems. Secondly, the statement should, once you have seen it, be completely obvious. The reaction of the reader might well be one of faint envy: Why haven’t I noticed this before? And thirdly, on an esthetic level, the Lemma – including its proof – should be beautiful!”

Interestingly, Aigner and Ziegler were building up to describing a result of Viennot’s – the Gessel-Lindström-Viennot Lemma – as a fundamental lemma! (I hope to talk about that lemma in a later post.)

Anyway, Flajolet’s Fundamental Lemma that I will describe and prove below is about expressing the weighted count of paths that look like

as a continued fraction

Next time I’ll give a few examples, including the connection with reverse Bessel polynomials.

Motzkhin paths

We consider Motzkhin paths, which are like Dyck paths and Schröder paths we considered last time, but here the flat paths have length .

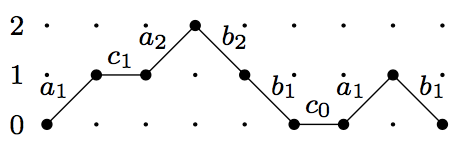

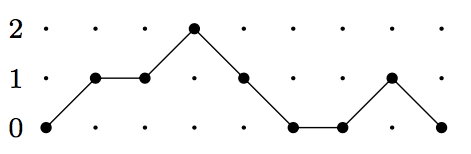

A Motzkhin path, then, is a lattice path in starting at , having steps in the direction , or . The path finishes at some . Here is a Motzkhin path.

(Actually at this point the length of each step is a bit of a red herring, but let’s not worry about that.)

We want to count weighted paths, so we’re going to have to weight them. We’ll do it in a universal way to start with. Let , and , be three sets of commuting indeterminates. Now weight each step in a path in the following way. Each step going up to level will be given the weight ; each step going down from level will be given the weight ; and each flat step at level will be given weight . Here’s the path from above with the weights marked on it.

The weight of a path is just the product of the weights of each of its steps, so the weight of the above path is .

If you try to start writing down the sum of the weightings of all Motzkhin paths you’ll get a power series that begins

Flajolet’s Fundamental Lemma will give us a formula for this power series.

Flajolet’s Fundamental Lemma

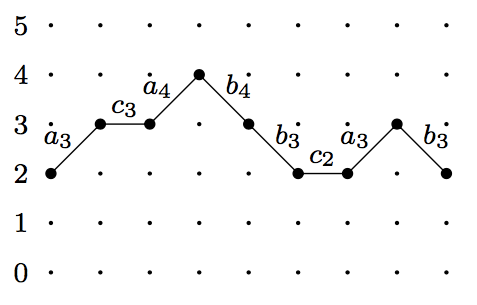

In order to prove the result about the enumeration of weightings of all paths we will need to consider slightly more general paths that don’t just start on the -axis. So define a –path to be like a Motzkhin path except that it starts at some point , for , does not go below the line nor above the line and finishes at some point . Let denote the set of all –paths.

Here is a –path with the weights marked on. Of course this is also, for instance, a –path.

We want the weighted sum of all Motzkhin paths, so in order to calculate that we will take to be the sum of all weights of -paths: There is a beautifully simple expression for .

Observe first that any path in is constrained to lie at level so must simply be a product of flat steps which all have weight , thus

Given two paths we can multiply them together simply by placing after . The above pictured example is the product of three paths in , the middle one being a flat path. Weighting is clearly preserved by this multiplication: .

An indecomposable -path is a path which only returns to level at its finishing point, i.e. as the name suggests, it can not be decomposed into a non-trivial product. It is clear that any path uniquely decomposes as a product of indecomposable paths. There are two types of non-trivial indecomposable -paths: there is the single flat step; and there are the paths which are an up step followed by a path in followed by a down step back to level . We let be the set of non-trivial indecomposable -paths.

This all leads to the following argument to deduce an expression for the weighted count of all -paths.

This is a lovely recursive expression for the weighted count . Using the fact that we gave above, we obtain the following.

Lemma

Now taking and letting we get the following continued fraction expansion for the weighted count of all Motzkhin paths starting at level .

Flajolet’s Fundamental Lemma

How lovely and simple is that?

Next time I’ll give some examples and applications which include the Dyck paths and Scröder paths we looked at previously.

Re: Lattice Paths and Continued Fractions I

Personally I’d like nothing better than a porism.

But since Flajolet got a lemma and I’m feeling faintly envious, who is this Flajolet? Phillipe Flajolet the French computer scientist?