I think I’ve worked out a lot of the relationship between large and geometry over , which makes some of the stuff above clearer.

First, let me recapitulate some of the underlying finite geometry, particularly over , and set up some notation.

Projective and polar spaces

I’ll work with projective spaces over and try not to suddenly start jumping back and forth between projective spaces and the underlying vector spaces as is my wont, at least not unless it really makes things clearer.

So we have an -dimensional projective space over . We’ll denote this by .

The full symmetry group of is , and from that we get subgroups and quotients (with unit determinant), (quotient by the centre) and (both). Over , the determinant is always (since that’s the only non-zero scalar) and the centre is trivial, so these groups are all the same.

In projective spaces over , there are points on every line, so we can “add” two any points and get the third point on the line through them. (This is just a projection of the underlying vector space addition.)

In odd characteristic, we get two other families of Lie type by preserving two types of non-degenerate bilinear form: symmetric and skew-symmetric, corresponding to orthogonal and symplectic structures respectively. (Non-degenerate Hermitian forms, defined over , also exist and behave similarly.)

Denote the form by . Points for which are isotropic. For a symplectic structure all points are isotropic. A form such that is called alternating, and in odd characteristic, but not characteristic , skew-symmetric and alternating forms are the same thing.

A line spanned by two isotropic points, and , such that is a hyperbolic line. Any space with a non-degenerate bilinear (or Hermitian) form can be decomposed as the orthogonal sum of hyperbolic lines (i.e. as a vector space, decomposed as an orthogonal sum of hyperbolic planes), possibly together with an anisotropic space containing no isotropic points at all. There are no non-empty symplectic anisotropic spaces, so all symplectic spaces are odd-dimensional (projectively—the corresponding vector spaces are even-dimensional).

There are anisotropic orthogonal points and lines (over any finite field including in even characteristic), but all the orthogonal spaces we consider here will be a sum of hyperbolic lines—we say they are of plus type. (The odd-dimensional projective spaces with a residual anisotropic line are of minus type.)

A quadratic form is defined by the conditions

i) , where is a symmetric bilinear form.

ii) for any scalar .

There are some non-degeneracy conditions I won’t go into.

Obviously, a quadratic form implies a particular symmetric bilinear form, by . In odd characteristic, we can go the other way: .

We denote the group preserving an orthogonal structure of plus type on an -dimensional projective space over by , by analogy with . Similarly we have , and . However, whereas is simple apart from exceptions, we usually have an index subgroup of , called , and a corresponding index subgroup of , called , and it is the latter that is simple. (There is an infinite family of exceptions, where is simple.)

Symplectic structures are easier—the determinant is automatically , so we just have and , with the latter being simple except for exceptions.

Just as a point with is an isotropic point, so any subspace with identically on it is an isotropic subspace.

And just as the linear groups act on incidence geometries given by the (“classical”) projective spaces, so the symplectic and orthogonal act on polar spaces, whose points, lines, planes, etc, are just the isotropic points, isotropic lines, isotropic planes, etc given by the bilinear (or Hermitian) form. We denote an orthogonal polar space of plus type on an -dimensional projective space over by .

In characteristic , a lot of this goes wrong, but in a way that can be fixed and mostly turns out the same.

1) Symmetric and skew-symmetric form are the same thing! There are still distinct orthogonal and symplectic structures and groups, but we can’t use this as the distinction.

2) Alternating and skew-symmetric forms are not the same thing! Alternating forms are all skew-symmetric (aka symmetric) but not vice versa. A symplectic structure is given by an alternating form—and of course this definition works in odd characteristic too.

3) Symmetric bilinear forms are no longer in bijection with quadratic forms: every quadratic form gives a unique symmetric (aka skew-symmetric, and indeed alternating) bilinear form, but an alternating form is compatible with multiple quadratic forms. We use non-degenerate quadratic forms to define orthogonal structures, rather than symmetric bilinear forms—which of course works in odd characteristic too. (Note also from the above that in characteristic an orthogonal structure has an associated symplectic structure, which it shares with other orthogonal structures.)

We now have both isotropic subspaces on which the bilinear form is identically , and singular subspaces on which the quadratic form is identically , with the latter being a subset of the former. It is the singular spaces which go to make up the polar space for the orthogonal structure.

To cover both cases, we’ll refer to these isotropic/singular projective spaces inside the polar spaces as flats.

Everything else is still the same—decomposition into hyperbolic lines and an anisotropic space, plus and minus types, inside , polar spaces, etc.

Over , we have that , , and are all the same group, as are and .

The vector space dimension of the maximal flats in a polar space is the polar rank of the space, one of its most important invariants—it’s the number of hyperbolic lines in its orthogonal decomposition.

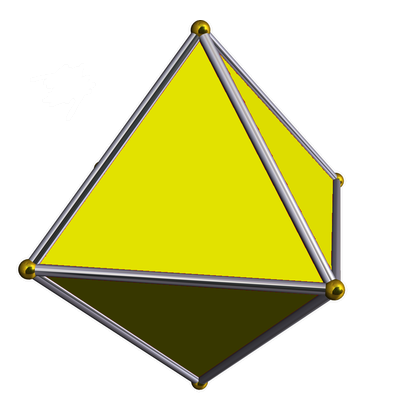

has rank . The maximal flats fall into two classes. In odd characteristic, the classes are preserved by but interchanged by the elements of with determinant . In even characteristic, the classes are preserved by , but interchanged by elements of .

Finally, I’ll refer to the value of the quadratic form at a point, , as the norm of , even though in Euclidean space we’d call it “half the norm-squared”.

Here are some useful facts about :

1a. The number of points is .

1b. The number of maximal flats is .

1c. Two maximal flats of different types must intersect in a flat of odd codimension; two maximal flats of the same type must intersect in a flat of even codimension.

Here two more general facts.

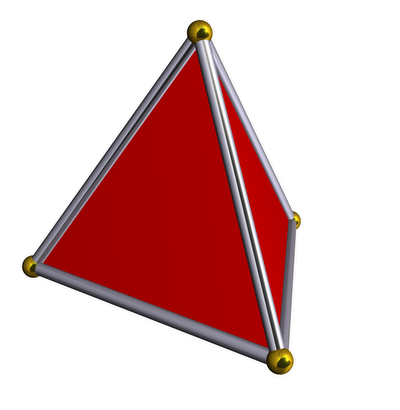

1d. Pick a projective space of dimension . Pick a point in it. The space whose points are lines through , whose lines are planes through , etc, with incidence inherited from , form a projective space of dimension .

1e. Pick a polar space of rank . Pick a point in it. The space whose points are lines (i.e. -flats) through , whose lines are planes (i.e. -flats) through , etc, with incidence inherited from , form a polar space of the same type, of rank .

The Klein correspondence at breakneck speed

The bivectors of a -dimensional vector space constitute a -dimensional vector space. Apart from the zero bivector, these fall into two types: degenerate ones which can be decomposed as the wedge product of two vectors and therefore correspond to planes (or, projectively, lines); and non-degenerate ones, which, by, wedging with vectors on each side give rise to symplectic forms. Wedging two bivectors gives an element of the -dimensional space of -vectors, and, picking a basis, the single component of this wedge product gives a non-degenerate symmetric bilinear form on the -dimensional vector space of bivectors, and hence, in odd characteristic, an orthogonal space, which turns out to be of plus type. It also turns out that this can be carried over to characteristic as well, and gives a correspondence between and , and isomorphisms between their symmetry groups. It is precisely the degenerate bivectors that are the ones of norm , and we get the following correspondence:

Here, “plane pencil” is all the lines that both go through a particular point and lie in a particular plane: effectively a point on a plane. The two type of plane in are two families of maximal flats, and they correspond, in , to “all the lines through a particular point” and “all the lines in a particular plane”.

From fact 1c above, in we have that two maximal flats of of different type must either intersect in a line or not intersect at all, corresponding to the fact in that a point and a plane either coincide or don’t; while two maximal flats of the same type must intersect in a point, corresponding to the fact in that any two points lie in a line, and any two planes intersect in a line.

Triality zips past your window

In , you may observe from facts 1a and 1b that the following three things are equal in number: points; maximal flats of one type; maximal flats of the other type. This is because these three things are cycled by the triality symmetry.

Counting things over

Over , we have the following things:

2a. has planes, each containing points and lines. It has (dually) points, each contained in lines and planes. It has lines, each containing points and contained in planes.

2b. has points, corresponding to the lines of , and planes, corresponding to the points and planes of . There’s lots and lots of other interesting stuff, but we will ignore it.

2c. has points and -spaces, i.e. two families of maximal flats containing elements each. A projective -space has points, so if we give it an orthogonal structure of plus type, it will have points of norm .

mod

Now we move onto the second part.

We’ll coordinatise the lattice so that the coordinates of its points are of the following types:

a) All integer, summing to an even number

b) All integer+, summing to an odd number.

Then the roots are of the following types

a) All permutations of

b) All points like with an odd number of minus signs.

We now quotient by . The elements of the quotient can by represented by the following:

a) All coordinates are or , an even number of each.

b) All coordinates are with either or minus signs.

c) Take an element of type b and put a star after it. The meaning of this is: you can replace any coordinate and replace it with , or any coordinate and replace it with , to get an lattice element representing this element of .

This is an -dimensional vector space over .

Now we put the following quadratic form on this space: is half the Euclidean norm-squared, mod . This gives rise to the following bilinear form: the Euclidean dot product mod . This turns out to be a perfectly good non-degenerate quadratic form of plus type over .

There are elements of norm , and these correspond to roots of , with roots per element (related by switching the sign of all coordinates).

a) Elements of shape are already roots in this form.

b) Elements of shape correspond to the roots obtained by taking the complement (replacing all s by and vice versa) and then changing the sign of one of the s.

c) Elements in which all coordinates are with either or minus signs are already roots, and by switching all the signs we get the half-integer roots with or minus signs.

There are non-zero elements of norm , and these all correspond to lattice points in shell , with lattice points per element of the vector space.

a) There are elements of shape . We get lattice points by changing an even number of signs (including ). We get another lattice points by taking the complement and then changing an odd number of signs.

b) There is element of shape . This corresponds to the lattice points of shape .

c) There are elements like , with or minus signs. We get actual lattice points by replacing by in one coordinate, and another by changing the signs of all coordinates.

This accounts for all points in shell .

Isotropic

Anisotropic

Since the quadratic form in comes from the quadratic form in Euclidean space, it is preserved by the Weyl group . In fact the homomorphism is onto, although (contrary to what I said in an earlier comment) it is a double cover—the element of that reverses the sign of all coordinates is a (in fact, the) non-trivial element element of the kernel.

Large lattices

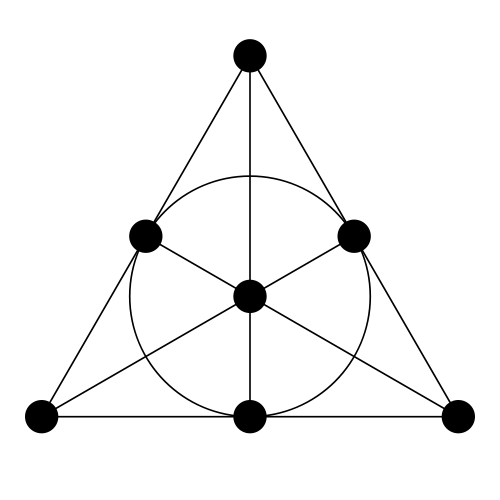

Pick a Fano plane structure on a set of seven points.

Here is a large containing :

(where )

where , , lie on a line in the Fano plane

where , , , lie off a line in the Fano plane.

Reduced to mod , these come to

i)

ii) where , , lie on a line in the Fano plane. E.g. .

iii) where , , , lie off a line in the Fano plane. E.g. .

Each of these corresponds to elements of the large roots.

Some notes on these points:

1) They’re all isotropic, since they have a multiple of non-zero entries.

2) They’re mutually orthogonal.

a) Elements of types ii and iii are all orthogonal to because they have an even number of ones (like all all-integer elements).

b) Two elements of type ii overlap in two places: and the point of the Fano plane that they share.

c) If an element of type ii and an element of type iii are mutual complements, obviously they have no overlap. Otherwise, the complement of is an element of type ii, so overlaps with it in exactly two places; hence overlaps with itself in the other two non-zero places of .

d) From , given two elements of type iii, one will overlap with the complement of the other in two places, hence (by the argument of c) will overlap with the other element itself in two places.

3) Adjoining the zero vector, they give a set closed under addition.

The rule for addition of all-integer elements is reasonably straightforward: if they are orthogonal, then treat the s and s as bits and add mod . If they aren’t orthogonal, then do the same, then take the complement of the answer.

a) Adding to any of the others just gives the complement, which is a member of the set.

b) Adding two elements of type ii, we set to the component and the component corresponding to the point of intersection in the Fano plane, leaving the components where they don’t overlap, which are just the complement of the third line of the Fano plane through their point of intersection, and is hence a member of the set.

c) Each element of type iii is the sum of the element of type i and an element of type ii, hence is covered implicitly by cases a and b.

4) There are elements of the set.

a) There is .

b) There are corresponding to lines of the Fano plane.

c) There are corresponding to the complements of lines of the Fano plane.

From the above, these elements form a maximal flat of . (That is, points projectively, forming a projective -space in a projective -space.)

That a large lattice projects to a flat is straightforward:

First, as a lattice it’s closed under addition over , so should project to a subspace over .

Second, since the cosine of the angle between two roots of is always a multiple of , and the points in the second shell have Euclidean length , the dot product of two large roots must always be an even integer. Also, the large roots project to norm points. So all points of the large should project to norm points.

It’s not instantly obvious to me that large should project to a maximal flat, but it clearly does.

So I’ll assume each corresponds to a maximal flat, and generally that everything that I’m going to talk about over lifts faithfully to Euclidean space, which seems plausible (and works)! But I haven’t proved it. Anyway, assuming this, a bunch of stuff follows.

Total number of large lattices

We immediately know there are large lattices, because there are maximal flats in , either from the formula , or immediately from triality and the fact that there are points in .

Number of large root systems sharing a given point

We can now bring to bear some more general theory. How many large root-sets share a point? Let us project this down and instead ask, How many maximal flats share a given point?

Recall fact 1e:

1e. Pick a polar space of rank . Pick a point in it. The space whose points are lines (i.e. -flats) through , whose lines are planes (i.e. -flats) through , etc, with incidence inherited from , form a polar space of the same type, of rank .

So pick a point in . The space of all flats containing is isomorphic to . The maximal flats containing in correspond to all maximal flats of , of which there are . So there are maximal flats of containing , and hence large lattices containing a given point.

We see this if we fix , and the maximal flats correspond to the ways of putting a Fano plane structure on points. Via the Klein correspondence, I guess this is a way to show that the Fano plane structures correspond to the points and planes of .

Number of large root system disjoint from a given large root system

Now assume that large lattices with non-intersecting sets of roots correspond to non-intersecting maximal flats. The intersections of maximal flats obey rule 1c:

1c. Two maximal flats of different types must intersect in a flat of odd codimension; two maximal flats of the same type must intersect in a flat of even codimension.

So two -flats of opposite type must intersect in a plane or a point; if they are of the same type, they must intersect in a line or not at all (the empty set having dimension ).

We want to count the dimension intersections, but it’s easier to count the dimension intersections and subtract from the total.

So, given a -flat, how many other -flats intersect it in a line?

Pick a point in . The -flats sharing that point correspond to the planes of . Then the set of -flats sharing just a line through with our given -flat correspond to the set of planes of sharing a single point with a given plane. By what was said above, this is all the other planes of the same type (there’s no other dimension these intersections can have). There are of these ( planes minus the given one).

So, given a point in the -flat, there are other -flats sharing a line (and no more) which passes through the point. There are points in the -flat, but on the other hand there are points in a line, giving -spaces sharing a line (and no more) with a given -flat.

But there are a total of -flats of a given type. If of them is a given -flat, and of them intersect that -flat in a line, then don’t intersect the -flat at all. So there should be large lattices whose roots don’t meet the roots of a given large lattice.

Other numbers of intersecting roots systems

We can also look at the intersections of large root systems with large root systems of opposite type. What about the intersections of two -flats in a plane? If we focus just on planes passing through a particular point, this corresponds, in , to planes intersecting in a line. There are planes intersecting a given plane in a line (from the Klein correspondence—they correspond to the seven points in a plane or the seven planes containing a point of ). So there are -flats of which intersect a given -flat in a plane containing a given point. There points to choose from, but points in a plane, meaning that there are -flats intersecting a given -flat in a plane. A plane has points, so translating that to lattices should give shared roots.

That leaves -flats intersecting a given -flat in a single point, corresponding to shared roots.

A couple of points here related to triality. Under triality, one type of maximal flat gets sent to the other type, and the other type gets sent to singular points (-flats). The incidence relation of “intersecting in a plane” gets sent to ordinary incidence of a point with a flat. So the fact that there are maximal flats that intersect a given maximal flat in a plane is a reflection of the fact that there are points in a maximal flat (or, dually, maximal flats of a given type containing a given point).

The intersection of two maximal flats of the same type translates into a relation between two singular points. Just from the numbers, we’d expect “intersection in a line” to translate into “orthogonal to”, and “disjoint” to translate into “not orthogonal to”.

In that case, a pair of maximal flats intersecting in a (flat) line translates to mutually orthogonal flat points—whose span is a flat line. Which makes sense, because under triality, -flats transform to -flats, reflecting the fact that the central point of the diagram (representing lines) is sent to itself under triality.

In that case, two disjoint maximal flats translates to a pair of non-orthogonal singular points, defining a hyperbolic line.

Fixing a hyperbolic line (pointwise) obviously reduces the rank of the polar space by , picking out a subgroup of . By the Klein correspondence, is isomorphic to , which is just the automorphism group of —i.e., here, the automorphism group of a maximal flat. So the joint stabiliser of two disjoint maximal flats is just automorphisms of one of them, which forces corresponding automorphisms of the other. This group is also isomorphic to the symmetric group , giving all permutations of the coordinates (of the lattice).

(My guess would be that the actions of on the two maximal flats would be related by an outer automorphsm of , in which the action on the points of one flat would match an action on the planes of the other, and vice versa, preserving the orthogonality relations coming from the symplectic structure implied by the orthogonal structure—i.e. the alternating form implied by the quadratic form.)

Nearest neighbours

We see this “non-orthogonal singular points” “disjoint maximal flats” echoed when we look at nearest neighbours.

Nearest neighbours in the second shell of the lattice are separated from each other by an angle of , so have a mutual dot product of , hence are non-orthogonal over .

Let us choose a fixed point in the second shell of . This has as our chosen representative in our version of , which has the convenient property that it is orthogonal to the all-integer points, and non-orthogonal to the half-integer points. The half-integer points in the second shell are just those that we write as in our notation, where the means that we should replace any by or replace any by to get a corresponding element in the second shell of the latttice, and where we require or minus signs in the notation, to correspond two points in the lattice with opposite signs in all coordinates.

Now, since each reduced isotropic point represents points of the second shell, merely saying that two reduced points have dot product of is not enough to pin down actual nearest neighbours.

But very conveniently, the sets of are formed in parallel ways for the particular setup we have chosen. Namely, lifting to a second-shell element, we can choose to put the in each of the coordinates, with positive or negative sign, and lifting an element of the form to a second-shell element, we can choose to put the in each of the coordinates, with positive or negative sign.

So we can line up our conventions, and choose, e.g., specifically , and choose neighbours of the form , with an even number of minus signs.

This tells us we have nearest neighbours, corresponding to the isotropic points of half-integer form. Let us call this set of points .

Now pick one of those isotropic points, call it . It lies, as we showed earlier, in maximal flats, corresponding to the plane flats of , and we would like to understand the intersections of these flats with : that is, those nearest neighbours which belong to each large lattice.

In any maximal flat, i.e. any -flat, containing , there will be lines passing through , each with other points on it, totalling which, together with itself form the points of a copy of .

Now, the sum of two all-integer points is an all-integer point, but the sum of two half-integer points is also an all-integer point. So of the two other points on each of those lines, one will be half-integer and one all-integer. So there will be half-integer points in addition to itself; i.e. the maximal flat will meet in points; hence the corresponding large lattice will contain of the nearest neighbours of .

Also, because the sum of two half-integer points is not a half-integer point, no of those points will lie on a line.

But the only way that you can get points in a -space such that no of them lie on a line of the space is if they are the points that do not lie on a plane of the space. Hence the other points—the ones lying in the all-integer subspace—must form a Fano plane.

So we have the following: inside the projective -space of lattice elements mod , we have the projective -space of all-integer elements, and inside there we have the -space of all-integer elements orthogonal to , and inside there we have a polar space isomorphic to , and in there we have planes. And adding to each element of one of those planes gives the elements which accompany in the intersection of the isotropic half-integer points with the corresponding -flat, which lift to the nearest neighbours of lying in the corresponding large lattice.

Re: Integral Octonions (Part 11)

Idea:

Consider a scaled copy of the first shell in the second shell that contains , treated as twice the identity in the octonions. Note that any point on the second shell not in is adjacent to some point in .

Consider a point on the second shell that is adjacent to . This yields a unit octonion via scaling; call it . There are 64 possible values of , since each -orthoplex in the polytope is adjacent to other -orthoplexes.

The two sets

and

are copies of the first shell in the second shell. So we get a total of 128 pairs of disjoint copies of the first shell in the second shell where one of the copies is .

Thus, since each pair contains two shells, we get disjoint pairs by this procedure.

Does this match the descriptions given by the computer calculations?