Hypergraph Categories of Cospans

Posted by John Baez

guest post by Jonathan Lorand and Fabrizio Genovese

In the Applied Category Theory Seminar, we most recently read Brendan Fong’s article on decorated cospans. This construction is part of a larger framework, developed in Brendan Fong’s PhD thesis, for studying interconnected, open, network-style systems. A paradigmatic example: systems composed of electric circuits having input and output terminals, allowing for composition of smaller circuits into larger. An aim of Brendan’s framework is to give, for any such kind of system, a unified categorical way to describe both the formal, symbolic language of such systems (their “syntax”) as well as the behavior of the systems that these formal symbols represent (the “semantics”). For circuits: syntax is formal rules for combining circuit diagram nomenclature; semantics is a (mathematical) description of how real-life circuits behave in the presence of voltages, currents, etc.. Decorated cospans are a tool ideal for “syntax”; decorated corelations are designed to handle “semantics” and are flexible enough to model any so-called hypergraph category. We’ll focus on the former, and hint at the latter.

John Baez has written several nice blog posts already about decorated cospans, corelations, and his work with Brendan Fong on passive linear networks of circuits; we hope the present post navigates a course which complements these. We set the scene with hypergraph categories, then discuss (decorated) cospans, and give a very brief introduction to corelations.

We’d like to thank Brendan for his many helpful comments, his technical support, and diagram sharing. Also thanks to Brendan, Nina and the whole “Adjoint team” for a great seminar experience so far.

Hypergraph categories

The name “hypergraph category” is rather new, introduced in [F1] and [K]. The concept itself is apparently older, going back at least to Carboni and Walters.

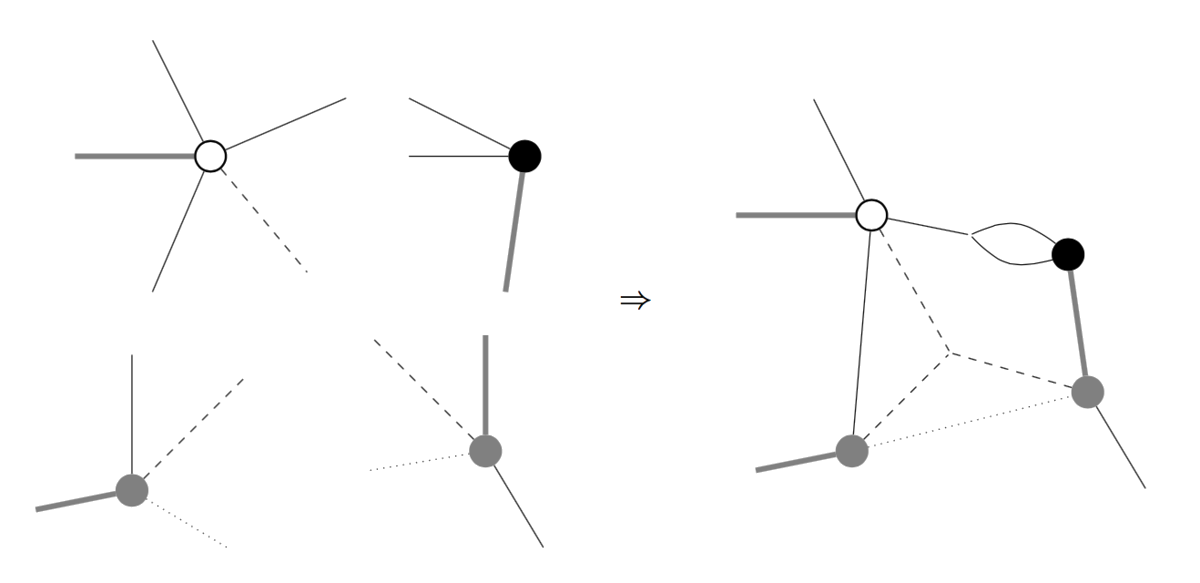

First of all, why “hypergraph”? There are several notions which fall under the name “hypergraph”, and we do not follow conventions too closely here. For us, a hypergraph is simply a kind of graph which has different types of nodes and edges, with edges allowed to be possibly “open” in the sense that they are attached only on one end to some node. Composition of such graphs to build new graphs is possible by connecting open edges together (though we only allow edges of the same type to connect). The following picture illustrates such a composition, with different types of edges indicated by different types of lines.

A hypergraph category is a categorical version of hypergraphs, where we think of edges as objects and nodes as morphisms. Here is a concise definition, we’ll then do some unpacking: a hypergraph category is a symmetric monoidal category such that each object is equipped with the structure of a special commutative Frobenius monoid, and such that these structures satisfy a certain compatibility with the monoidal product.

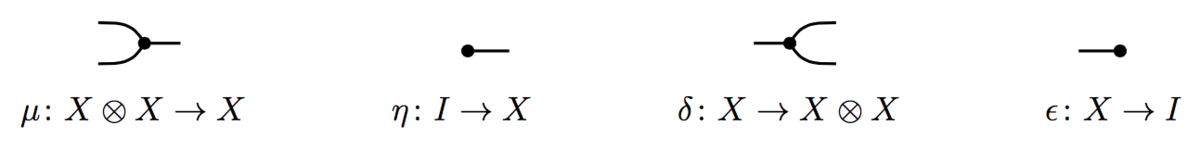

We’ll use the string diagram language for symmetric monoidal categories, and introduce four new symbols corresponding to (co)monoid maps. A special commutative Frobenius monoid structure (SCFM structure) on an object of a symmetric monoidal category is given by maps

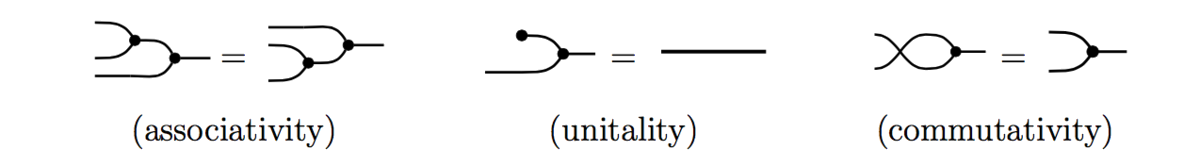

(called the multiplication, unit, comultiplication, and counit), satisfying the axioms of a commutative monoid

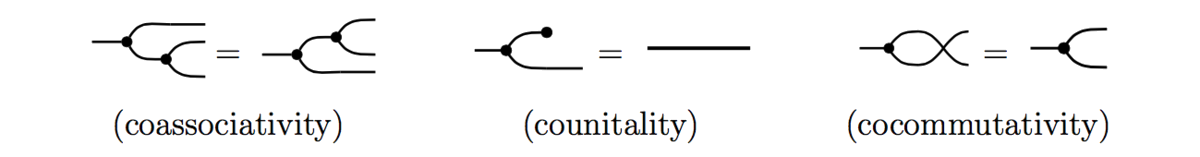

and cocommutative comonoid

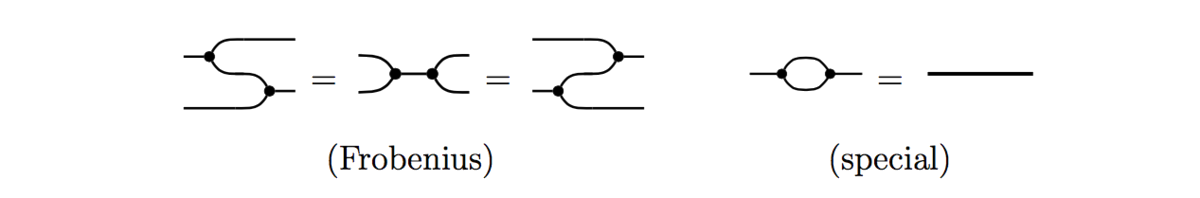

as well as the “Frobenius” and “special” axioms

This set of axioms is not minimal; in particular, if a monoid and comonoid structure satisfies the Frobenius law, then commutativity and cocommutativity imply each other. Thus the term “commutative” Frobenius monoid entails “bicommutativity”.

Suppose an object in carries a SCFM structure. A coherence result know as the “spider theorem” tells us, roughly, that any morphism described by a connected string diagram, and defined only using operations and canonical maps coming from and the maps , can be depicted simply as a “spider”: a diagram with one node, input legs and output legs.

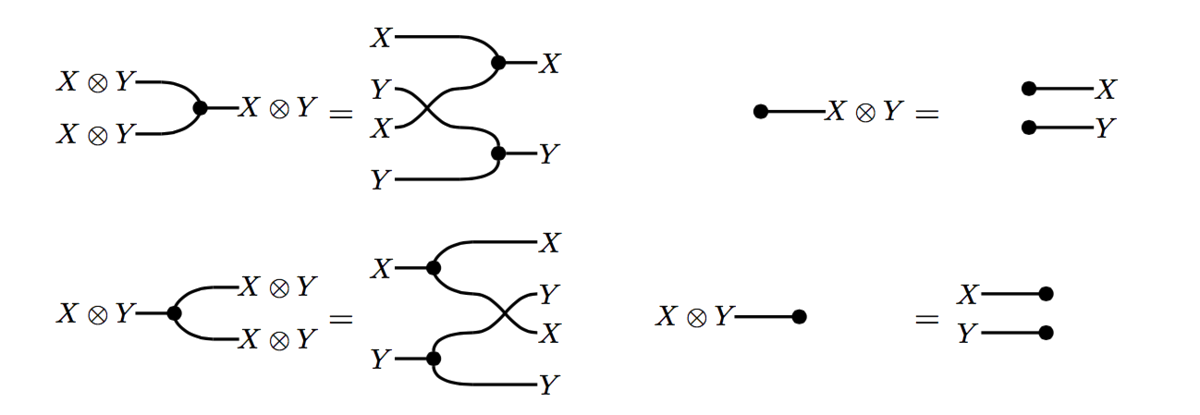

This result, though, is only about maps between monoidal powers of a single object . The interaction of SCFM structures on different objects of a hypergraph category is provided by the following compatibility axioms: in a hypergraph category we require

In this way one obtains a kind of category whose calculus of string diagrams reflects the initial intuition given by hypergraphs. More details, in particular on diagrammatics, can be found in [BGKSZ] and [K].

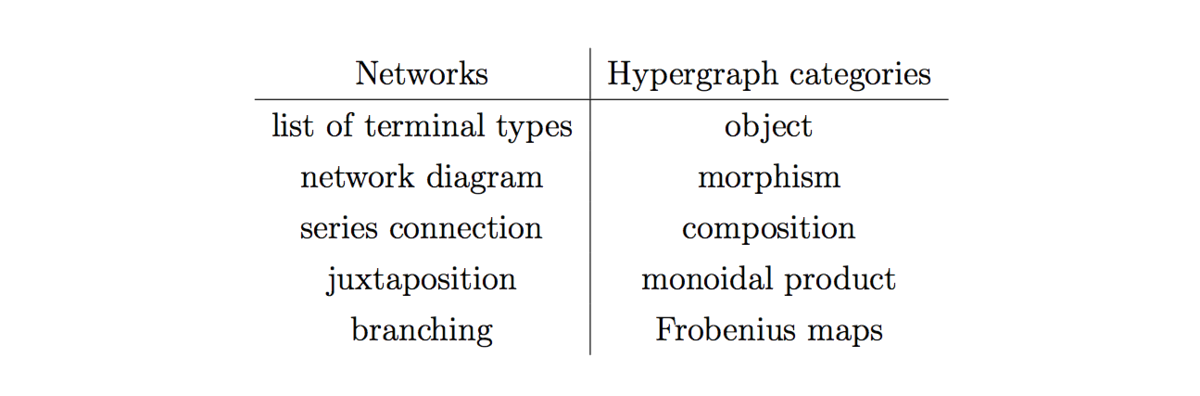

As indicated above, hypergraphs are a natural structure for describing open, network-like systems. The word “open” means that one has a notion of input, output and composition/interaction. Here is a summary of this “network intuition” in terms of hypergraph categories

One wishes also to compare/translate between different hypergraph categories. A hypergraph functor between hypergraph categories is a strong symmetric monoidal functor such that, for each object of , the SCFM structure on must coincide with the one induced by :

An equivalence of hypergraph categories is an equivalence of symmetric monoidal categories which is built of hypergraph functors.

An important remark about hypergraph categories is that the SCFM maps on each object in are not required to be natural in . Morphisms in need not interact in a coherent way with the SCFM structures. In particular, a given symmetric monoidal category may admit two hypergraph structures which are hypergraph inequivalent.

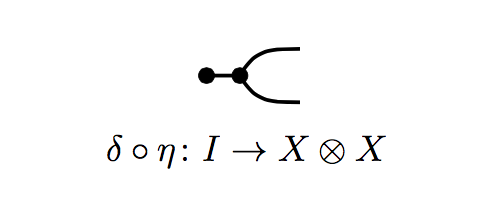

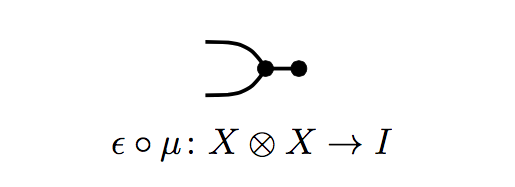

Another remark is that hypergraph categories are automatically compact closed, with every object self-dual: the maps

and

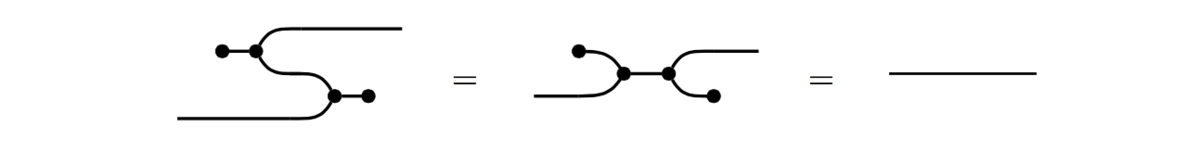

(think: cup and cap) satisfy

as well as the vertically reflected equations (think: snake!). The first equality uses the Frobenius law, the second the (co)unital laws.

Cospan Categories

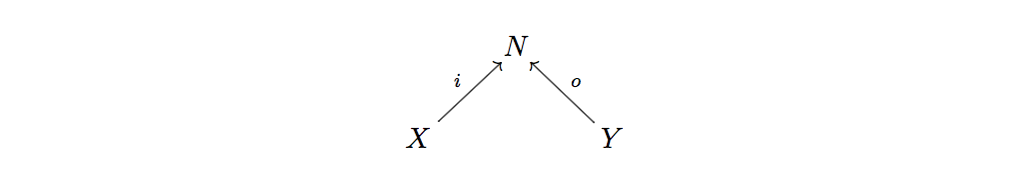

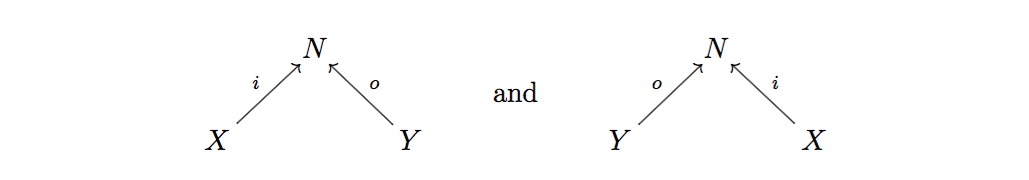

Cospans lead to hypergraph categories following a familiar construction. One starts with a category having finite colimits, viewing it as a symmetric monoidal category with the coproduct as monoidal product. From this we define a category whose objects are the objects of , and whose morphisms are cospans in

considered up to a notion of isomorphism. The source and target of the cospan are the “feet”, while is the “apex”. Cospans are isomorphic for us if they have the same feet and if there exists an isomorphism between their apexes which makes the evident triangles commute. The maps and (the “legs” of the cospan) are labeled to hint at the interpretation that we are thinking of as representing inputs, and as representing outputs.

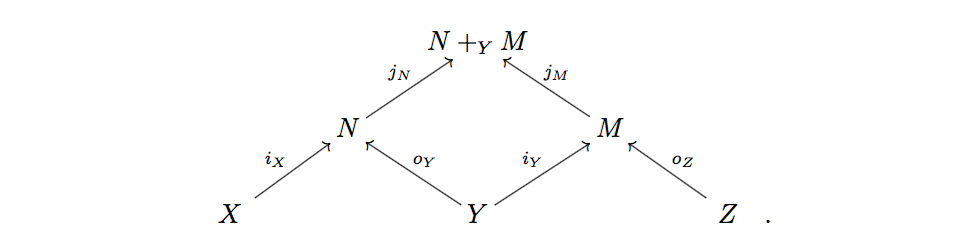

Composition of cospans and is given by taking a pushout over the shared foot

Considering only isomorphism classes of cospans makes this composition well-defined and associative, and one checks that this builds us a category. It’s called .

has a symmetric monoidal structure induced from , and comes with a canonical hypergraph structure. To see roughly how this works, note that we have an “identity on objects” embedding defined by sending a morphism in to the cospan . This gives us a copy of inside and induces a monoidal structure on .

The directional symmetry in the definition of a cospan means that cospans actually come in pairs

Call such cospans opposites of one another. Note that, alongside the above embedding, there is an analogous embedding , sending to .

For each object in we have the copairing and a unique map from our initial object in . The images of these morphisms under give us a multiplication map and a unit map for a commutative monoid structure on . By defining comultiplication and counit via the cospans which are opposite to and , respectively, one obtains a SCFM on each object of , with compatibility making a hypergraph category.

As a simple example to play with, consider the category whose objects are the sets , , , , … and whose morphisms are functions between these sets. This category has finite colimits, with initial object and coproduct defined by

these make a symmetric strict monoidal category. We think of as the generator of the objects; all other objects may be built from this one using the coproduct (thinking of as the zero-th monoidal power of ). Graphically we depict as a black dot, and any object as a cloud of dots (since our monoidal product is strictly commutative, the order of how we juxtapose our dots doesn’t matter, so we just use “clouds”).

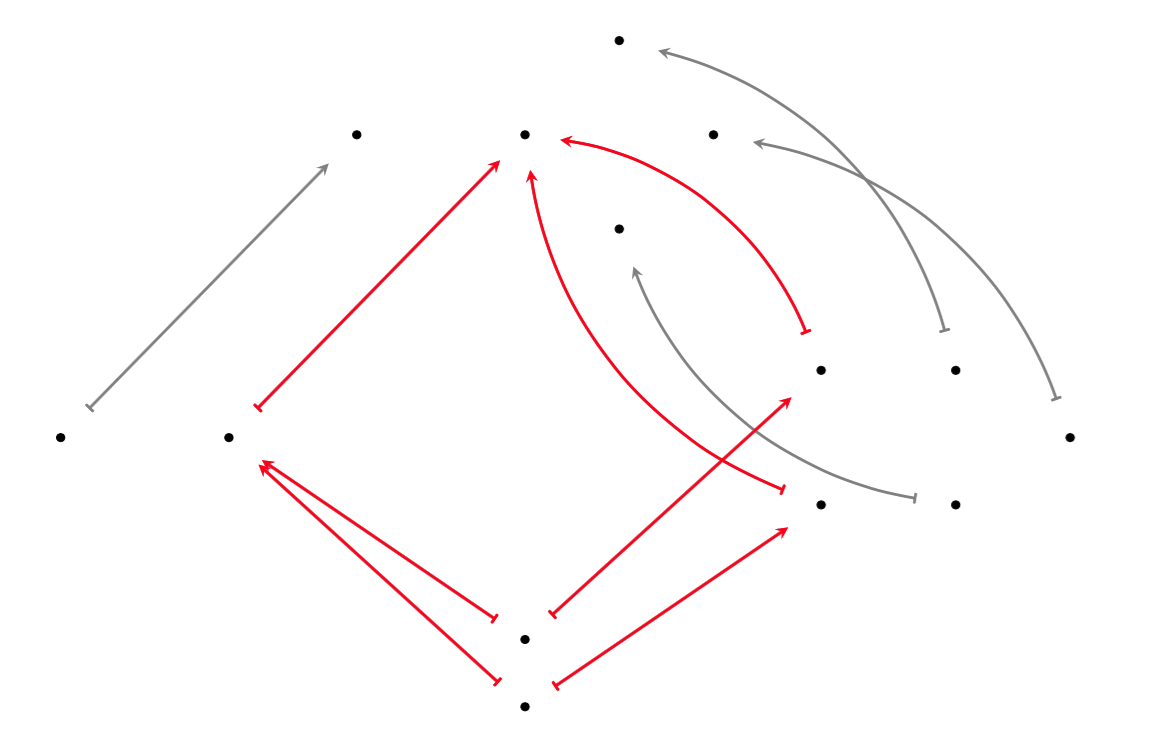

Suppose we are composing cospans and in . The pushout over the shared foot implements the merging of the two apexes according to the “instructions” given by the output function of the first cospan and the input function of the second, as illustrated below in red

In this image, the bottom “cloud” is , on the left is , on the right is , and above is , while and , and the maps from them, are not depicted.

Decorated cospans

In the setting of electrical circuits, one may view circuit diagrams as a set of nodes which is “decorated” by the other symbols of the circuit diagram. For given , this information may be encoded mathematically by specifying, for example, a set of edges E with target and source maps , as well as other information, such as an assignment of resistances to edges by specifying a function .

Thinking of the set of nodes as the apex of a cospan in , the images in of the feet and correspond to choices of input and output terminals, respectively, and the legs of the cospan allow further flexibility in connecting, for example, multiple inputs of one circuit to an output terminal of another, as illustrated above. John Baez’s blog post has nice examples of circuits being composed.

Decorated cospans are designed to capture this intuitive notion of composition of network diagrams. This must be done in such a way that the cospans and their decorations compose together in the desired manner.

Formally, Brendan achieves this using a lax monoidal functor to encode the decorations on the apexes of cospans in . (One may actually use any monoidal category in place of ). Given such a functor , he constructs a category of “-decorated cospans in ” where the objects are the objects of , and morphisms are represented by pairs consisting of a cospan in and an element of the image of the apex under . This element is the decoration of the apex. On the nose, morphisms in are isomorphism classes of such pairs; two such pairs are isomorphic if their constituting cospans are isomorphic via an isomorphism between their apexes which is also compatible with the decorations: .

Composition of decorated cospans works, on representatives of morphisms in , by composing the constituent cospans and composing the decorations and by sending to a decoration on the composed apex via the map

(recall that and denote the pushout maps involved in composing our cospans). A key point is that we can use the copairing to implement the “merging” of the decorations on and .

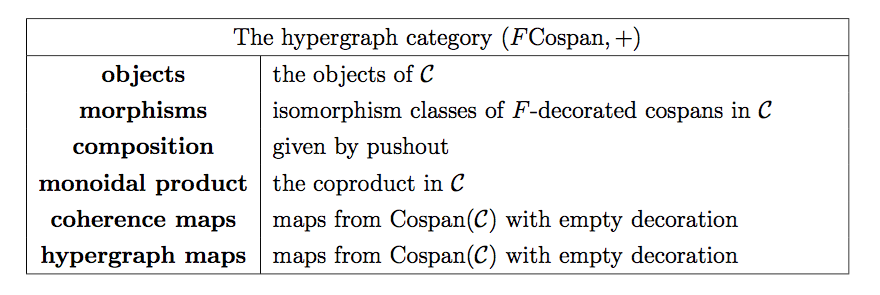

Under the assumptions that the “decoration category” , and , are braided (we keep these assumptions now), the category inherits a monoidal and hypergraph structure from . Here is a summary:

In [F1] (see Theorem 4.1) a method is given for constructing hypergraph functors between decorated cospan categories and , starting from the data of a natural transformation which relates and to and .

In [F2], decorated cospans are generalized to decorated corelations, and in this setting a theorem is proved which is analogous to the one mentioned above. This gives, in particular, a way of constructing functors from hypergraph categories of decorated cospans (think: syntax) to hypergraph categories of corelations (think: semantics).

Although we won’t have the space to explain decorated corelations properly, we’ll conclude our post by introducing the basic idea of corelations and indicating their potential for describing the “semantics”, or behavior, of open, network-like systems.

Corelations

The corelation approach to describing the behavior of open systems is linked to the idea of “black-boxing”. Suppose one has two different circuit diagrams - described in a decorated cospan category as above - which have the same set of input and output terminals and , and suppose we build these circuits. The real-life circuits will impose certain relations on the values of the voltages and currents which may be simultaneously measured at all of the terminals. Not every configuration of possible values is realizable because circuits obey certain laws, such as Ohm’s law relating currents, voltages and resistances.

Note that two different circuits might impose the same relations between their terminals. With respect to an agreed upon mode of measurement, the relations imposed by a circuit on its terminals may be called the (external) “behavior” of a circuit. We’ll say that two circuits behave the same way if they are indistinguishable by making measurements at their terminals. In other words, if each circuit were covered by an opaque black box, with only the terminals exposed, we would not know which circuit is which.

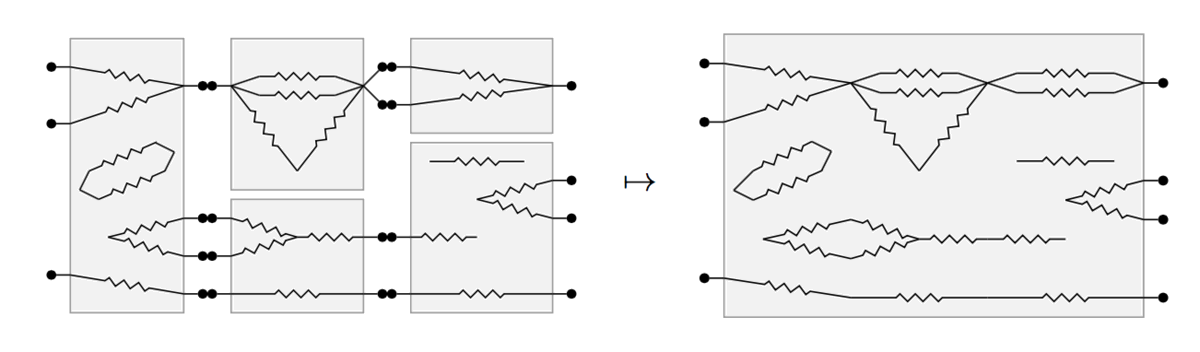

Decorated corelations are designed to capture exactly the information about the “black-box behavior” of open, network-style systems. Brendan gives at least two reasons why one might wish to keep track only of this “behavioral” information, rather than all of the internal workings of components of open systems. One reason is conceptual clarity: the focus is kept on the behaviorally relevant information. A second reason is computational: when smaller components are composed into larger, the amount of syntactical information may increase explosively, while semantically relevant information may be more stable. As a simplified illustration: in the below composition of circuit diagrams, the parts of the resulting larger circuit which have no paths to any terminals are not relevant for the behavior of the circuit.

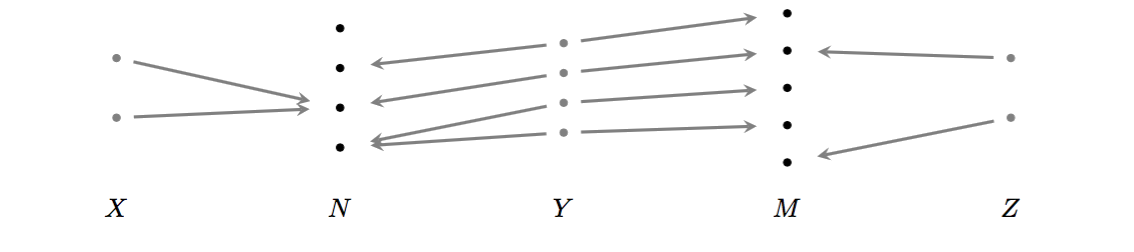

To give a sketch of how corelations work, let’s use the category FinSet mentioned above. Suppose we have cospans in FinSet and , ready to be composed as so

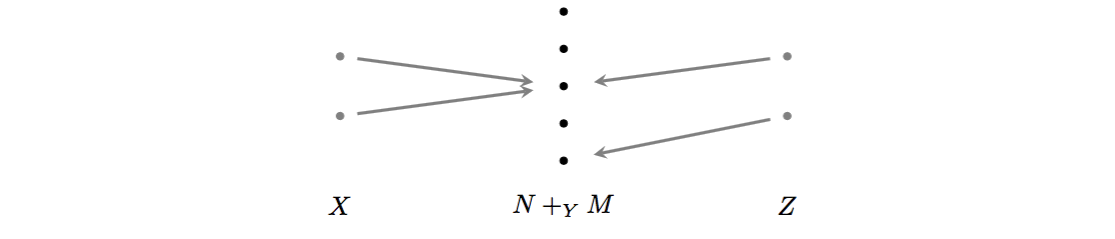

Their composite

is the cospan . The union of the images of the legs of this cospan is precisely the image of the copairing . Points outside of this image may be irrelevant, we may wish to “discard” them. A way of implementing “discarding” is to focus our attention on cospans for which is surjective. These are called corelations. To compose corelations and , we compose them as cospans to obtain and then restrict the map to its “surjective part”, to obtain again a corelation.

Factorization systems in a category give a way to make this idea precise and general; in [F2] factorization systems are used define a general notion of corelation which is modeled on the above example. Then, given a category with finite colimits and a factorization system with suitable properties, one can build a hypergraph category where objects are those of and morphisms are so-called -corelations. As in the case of cospans, corelations can be decorated, leading to decorated corelation categories. The scope of this construction turns out to be quite general: in [F3] it is proved that any hypergraph category is hypergraph equivalent to some decorated corelation category.

Further reading

[BF] Baez, J., Fong, B., A compositional framework for passive linear networks, arXiv:1504.05625

[BGKSZ] F. Bonchi, F. Gadducci, A. Kissinger, P. Sobocinski, F. Zanasi, Rewriting modulo symmetric monoidal structure, Proceedings of Logic in Computer Science, LICS16 (2016), 710–719

[F1] Fong, B., Decorated Cospans, Theory and Applications of Categories 30 (2015), 1096–1120.

[F2] Fong, B., Decorated Corelations, arXiv:1703.09888

[F3] Fong, B., PhD Thesis, arXiv:1609.05382

[K] Kissinger, A., Finite matrices are complete for (dagger-)hypergraph categories, arXiv:1406.5942.

Re: Hypergraph Categories of Cospans

I see no pictures when I view this page with experimental Firefox 60 (Nightly 60.0a1 (2018-02-21) (32-bit)), but it works fine in Chrome. The problem seems to be that the page is secure (“https”) while the images are not (“http”). The console log has lots of error messages like

This seems like an overly aggressive security fix that will break lots of old pages but the security concerns could probably be complied with.