Double Limits: A User’s Guide

Posted by Emily Riehl

Guest post by Matt Kukla and Tanjona Ralaivaosaona

Double limits capture the notion of limits in double categories. In ordinary category theory, a limit is the best way to construct new objects from a given collection of objects related in a certain way. Double limits, extend this idea to the richer structure of double categories. For each of the limits we can think of in an ordinary category, we can ask ourselves: how do these limits look in double categories?

In ordinary category theory, many results can be extended to double categories. For instance, in an ordinary category, we can determine if it has all limits (resp. finite limits) by checking if it has all products and equalizers (resp. binary products, a terminal object, and equalizers) (see Thm 5.1.26 in [3]). In a double category, we need to introduce a new notion of limit, known as a tabulator. One of the main theorems by Grandis and Paré states that a double category has all small double limits if and only if it has small double products, double equalizers, and tabulators. Therefore, these components are sufficient to construct small double limits. To explain this concept thoroughly, we will introduce their definitions in this post. There are various definitions depending on your focus, but for the sake of simplicity, this guide aims to be accessible to anyone with a background in category theory. For an introduction to double categories, see here.

We give an overview of how limits behave in this two-dimensional setting, following Grandis and Paré’s “Limits in double categories.” In particular, we make several definitions more explicit for use in further computations.

Introduction

Recall that double categories consist of two types of morphisms, horizontal and vertical, which interact in a compatible way. Often, composition of one arrow type is weaker than the other. Therefore, we may also think of limits in two different directions. However, limits with respect to the weaker class of morphisms tend to be badly behaved. Hence, in this post, we will only focus on horizontal double limits.

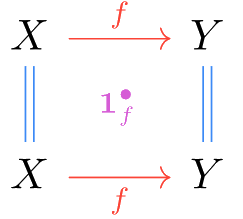

Throughout this article, we will refer to the class of morphisms with strong composition as “arrows,” written horizontally, with composition denoted by . The weaker arrows will be called “proarrows,” written as vertical dashed arrows, and with composition denoted by . Identity arrows/proarrows for an object will be written and respectively. Sometimes, we will also refer to the identity cell associated to an arrow . This is obtained by taking both proarrow edges to be the respective vertical identities on objects:

There’s an analogous construction for proarrows, but we won’t need it in this article.

Double limits are defined for double diagrams and a double diagram is a double functor from an indexing double category to an arbitrary double category . A limit for a given double diagram is a universal double cone over . This is a very high-level definition, but we will try to explain each unfamiliar term and illustrate it with examples.

The first thing we need to understand is a double diagram for which we take the limits.

Diagrams

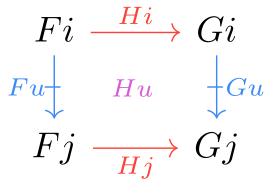

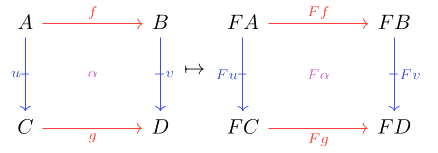

A double diagram in of shape is a double functor between double categories and . In strict double categories, a double functor is simultaneously a functor on the horizontal and vertical structures, preserving cells as well as their vertical compositions, horizontal compositions, identities. That is, for every cell ,

and for every composable pair of cells and

preserve horizontal compositions of cells: ,

preserve vertical compositions of cells: ,

preserve cell-wise horizontal identity: for each proarrow , ,

preserve cell-wise vertical identity: for each arrow , ,

We will also need the notion of a double natural transformation. These are defined componentwise, much in the same way as ordinary natural transformations. For double functors , a horizontal transformation is given by the following data:

horizontal -arrows for every object

an -cell for every proarrow in of the shape

Identities and composition are preserved.

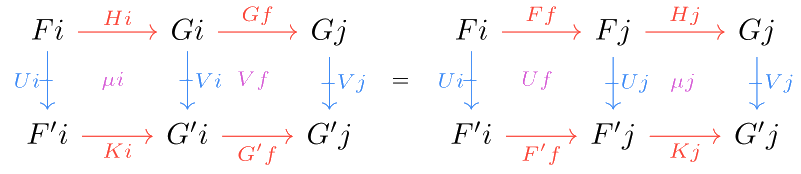

For every cell with proarrow edges and arrow edges , the component cells of and satisfy

Vertical transformations satisfy analogous requirements with respect to vertical morphisms, given Section 1.4 of [1].

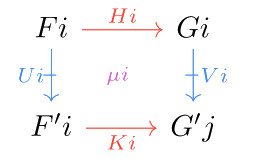

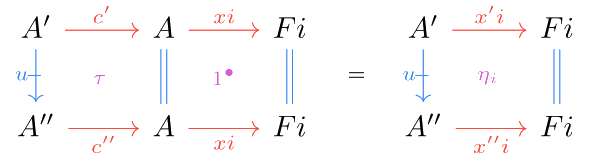

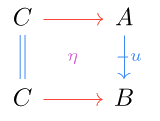

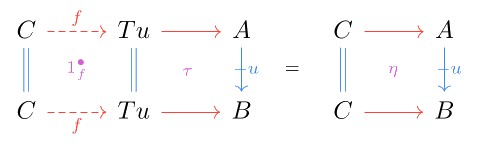

We will also use the notion of a modification to define double limits. Suppose we have double functors , horizontal transformations and vertical transformations . A modification is an assignment of an -cell to each object :

such that, for every horizontal , :

Double limits will be defined as a universal double cone. But what are cones or double cones in double categories? You may ask.

Like ordinary categories, cones for a functor in double categories also consist of an object and morphisms from to the objects , for each object of . Note that there two types of morphisms, those of horizontal direction or arrows and those of vertical direction or proarrows. The morphisms involved in cones are the horizontal ones but must be compatible with vertical ones. Let’s dive into the definition to see how that works.

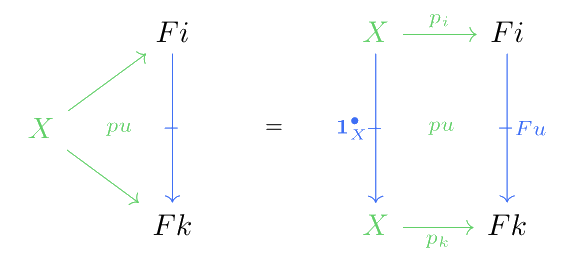

A double cone for a double functor consists of an with arrows for each object of , and cells for each every proarrow , satisfying the following axioms:

for each object in ,

for each composable pair of proarrows and in ,

for every cell in ,

Note that this implies that and . We can observe that the cells for every are made of two green arrows and , which is indeed a cell such that the horizontal source of is the identity proarrow .

For example, let’s take cones for the functor from an indexing double category which is the discrete double category (made of only two objects and ), to an arbitrary double category, defined such that and . Then, a double cone for is a candidate product for and .

Notice that the above description of a double cone satisfies the requirements of a horizontal transformation. We can consider a constant functor at an object of , then the data of a double cone with vertex is determined by a horizontal transformation . The componentwise definition of unrolls to precisely the conditions specified above.

We have now all the setup needed for defining double limits, since as we mentioned above, double limits are universal double cones. That is, a double cone for an underlying functor through which any other double cones factor.

Double Limits

Limits

Let be a double functor. The (horizontal) double limit of is a universal cone for .

Explicitly, this requires several things:

For any other double cone , there exists a unique arrow in with (where is the constant functor at the vertex of )

Let be double cones with a proarrow . For every collection of cell where is an object of , associated to components of each cone, which organize into a modification, there exists a unique -cell such that :

In other words, a cell built from a proarrow and the components of two cones (viewed as natural transformations) can be factored uniquely via and .

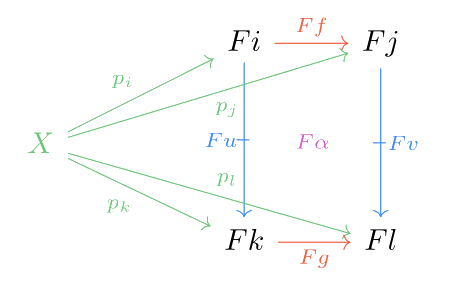

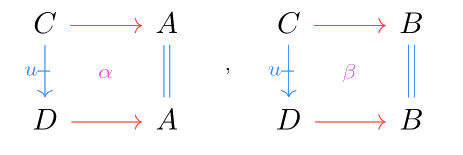

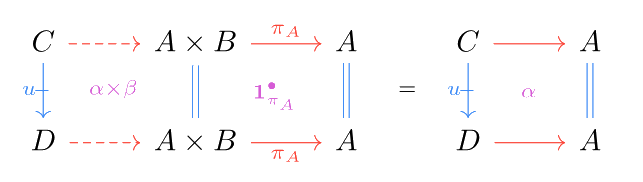

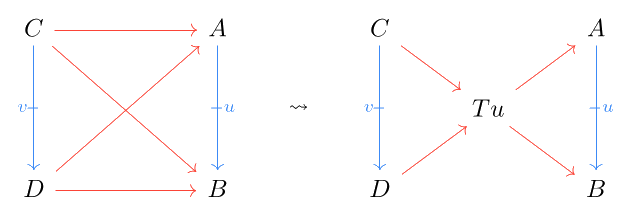

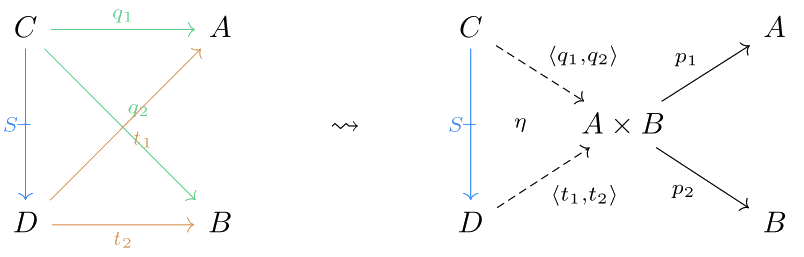

To get a better feel for double limits in practice, let’s examine (binary) products in a double category. Just as in 1-category theory, products are constructed as the double limit of the diagram (two discrete objects). Spelling out the universal properties of a double limit, the (double) product of objects consists of an object which satisfies the usual requirements for a product with respect to horizontal morphisms (with projection maps . Additionally, given cells as below:

there exists a unique cell such that

An identical condition must also hold for and .

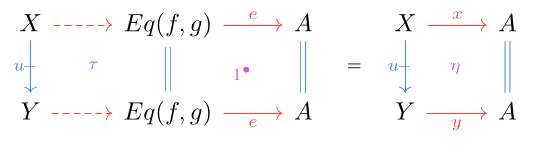

Equalizers can be extended to the double setting in a similar manner. Taking the double limit of the diagram yields double equalizers. For horizontal in , the double equalizer of and consists of an object equipped with a horizontal arrow , which is the equalizer of in the ordinary sense with respect to horizontal arrows. Additionally, for every cell with , there exists a unique such that :

Tabulators

Until now, we have considered examples of double limits of diagrams built from horizontal morphisms. Tabulators bring proarrows into the mix. They are an interesting case obtained as the limit over the diagram consisting of a single proarrow: .

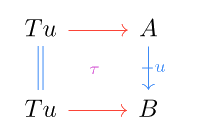

Suppose that is a proarrow. The tabulator of is the double limit of the diagram consisting of just . Unrolling the limit, this amounts to an object along with a cell :

such that, for any cell of the following shape,

there exists a unique horizontal morphism such that :

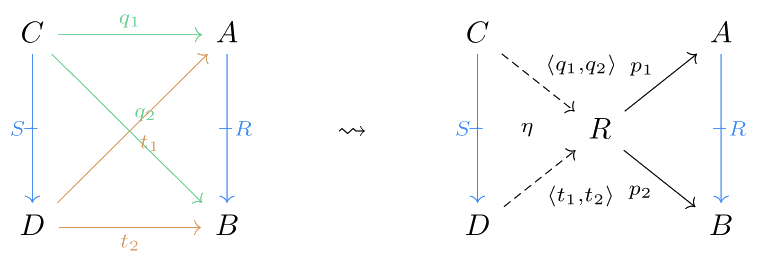

Additionally, any proarrow with horizontal morphisms to and forming a tetrahedron can be uniquely factored through :

In an ordinary category, the existence of all finite products and equalizers is enough to guarantee the existence of all limits. However, in the double setting, we need something extra: tabulators. The following result gives us a similar condition for limits in double categories.

Theorem (5.5 in [1]): A double category has all small double limits if and only if it has small double products, equalizers, and tabulators.

Examples in

In this section, we consider the double category of sets with functions as horizontal morphisms and relations as vertical morphisms, for more information see [1].

Tabulators

A tabulator for a proarrow or relation is itself with the projection maps and . For every other double cone of , there exists a unique function or arrow (), such that ; and for every relation and such that is also a double cone for , there exists a unique cell , such that .

Product

The double product of two sets and is the cartesian product with the usual projection maps and we also have the following:

References

[1] Grandis, Marco, and Robert Paré. "Limits in double categories." Cahiers de topologie et géométrie différentielle catégoriques 40.3 (1999): 162-220.

[2] Patterson, Evan. “Products in double categories, revisited.” arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.08990 (2024).

[3] Leinster, Tom. “Basic category theory.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1612.09375 (2016).|