Profunctor Optics: The Categorical View

Posted by John Baez

guest post by Emily Pillmore and Mario Román

In functional programming, optics are a compositional representation of bidirectional data accessors provided by libraries such as Kmett’s lens, or O’Connor’s mezzolens. Optics were originally called accessors or generalized functional references and appeared as a compositional solution to accessing fields of nested product types. As the understanding of functional references grew, different families of optics were introduced for a variety of different types (e.g. prisms for tagged unions or traversals for containers), culminating in a whole “glassery” of intercomposable accessors.

More recently, Milewski explained the profunctor formulation of these optics in terms of Tambara modules: profunctors endowed with additional structure that makes it interplay nicely with a monoidal action. Milewski explains how a unified profunctor representation of optics can be obtained following Pastro and Street’s “Doubles for monoidal categories”.

In this twelfth post for the Applied Category Theory School we will be presenting Bartosz Milewski’s post “Profunctor optics: the categorical view”. We will give an introduction to the topic of optics, and discuss some of the ideas developed during the course of the ACT Adjoint School 2019.

Lenses

The most obvious and famous data accessing pattern of this kind is a lens. The origin of lenses in category theory goes back to De Paiva’s Dialectica categories and Oles’ store shapes. Since then, they have appeared on wiring diagrams, supervised learning and compositional game theory; you can read Hedges’ blog post for a history of lenses. Their use as data accessors is described by Pickering, Gibbons and Wu.

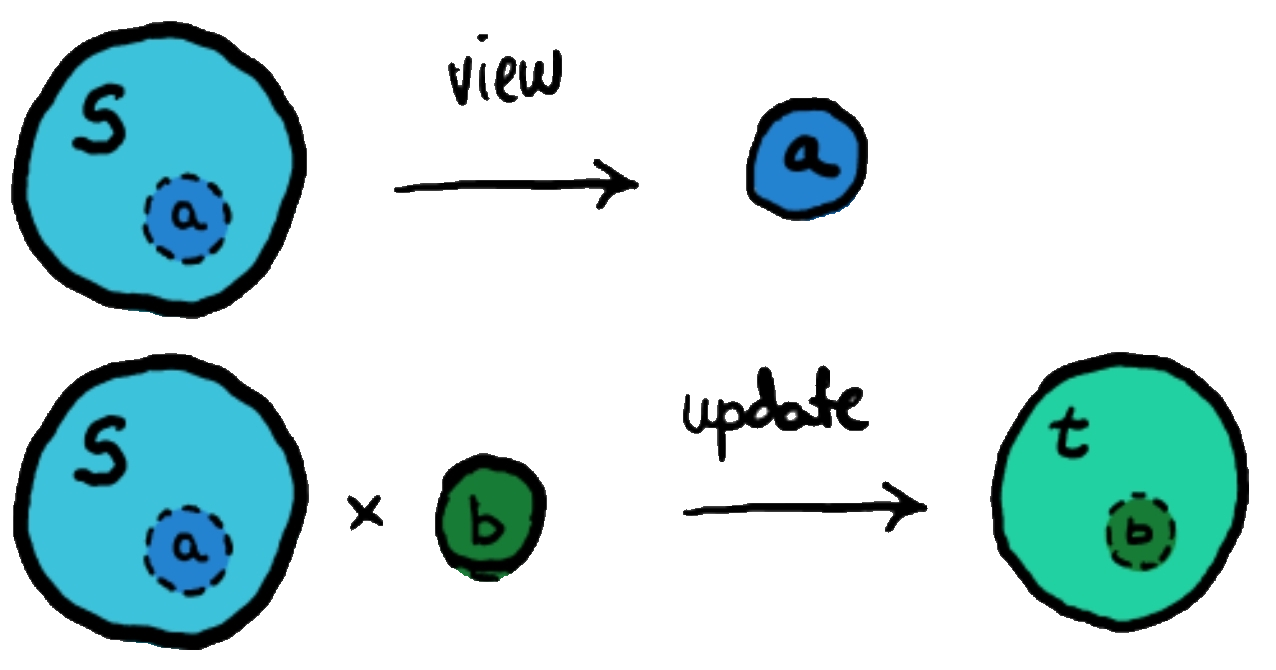

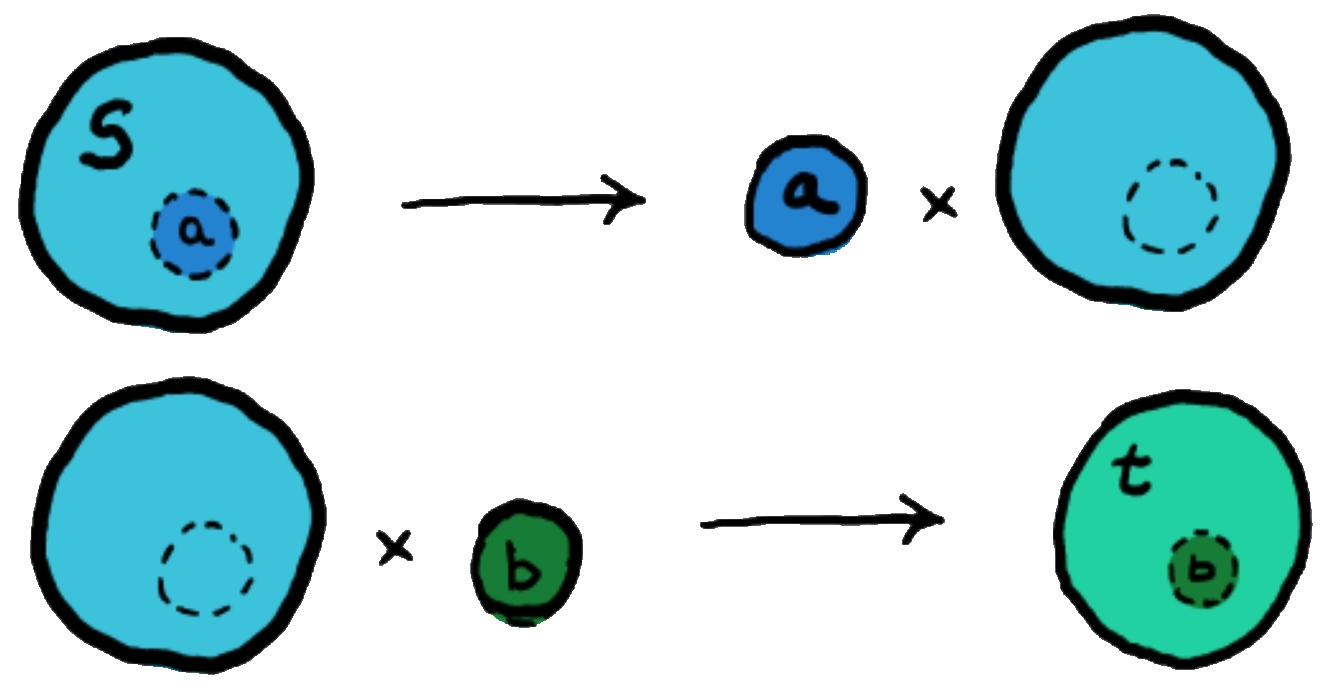

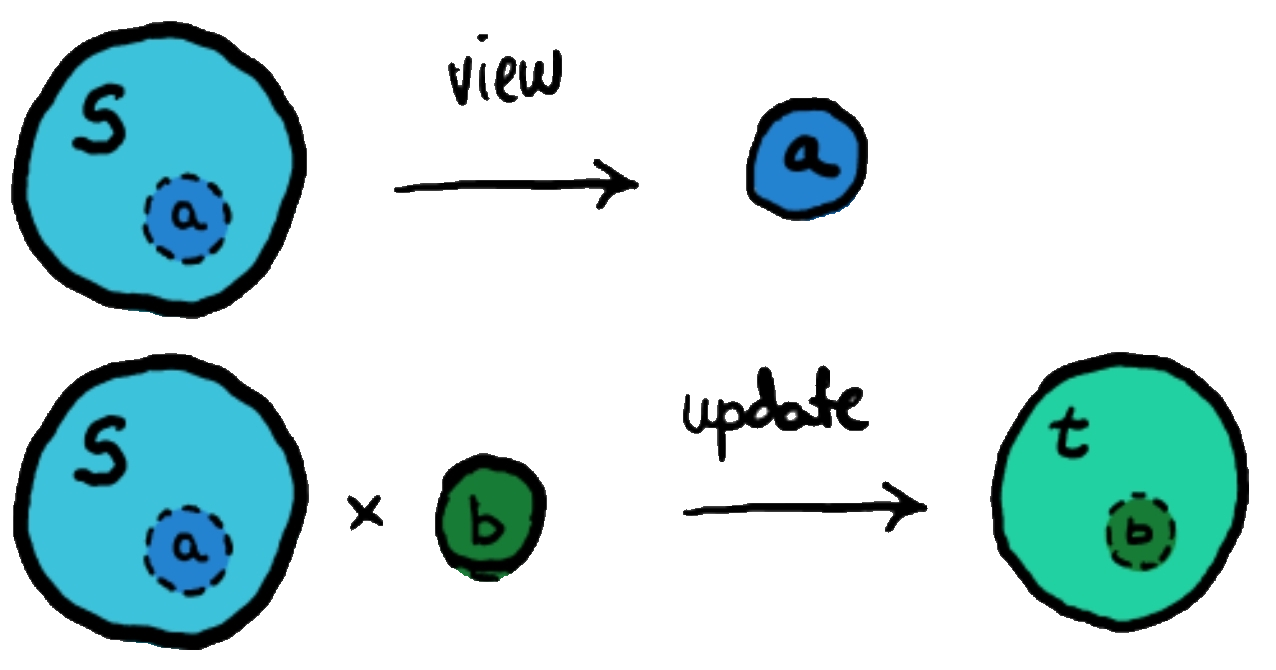

In functional programming, a lens between two pairs of types and consists of two functions and . We interpret as the type for the original record; is the type of the the updated record; is the type of the part of to be updated; is the type of the data that will replace ; the function is the view function; and is the update.

In a cartesian category , a lens from a pair of objects to a pair of objects is given by two morphisms: a view , and an update .

Example: suppose we have a data structure (or a set) representing postal addresses, with the ZIP code being a subfield of any postal address. We want to be able to view the ZIP code inside an address and to modify it, creating a new address. This can be encoded as a lens.

Or, in Haskell notation,

viewZip :: Postal -> ZipCode

updateZip :: (Postal, ZipCode) -> Postal

Lenses are optics, but not all optics are necessarily lenses. Let us describe other families of optics.

Prisms

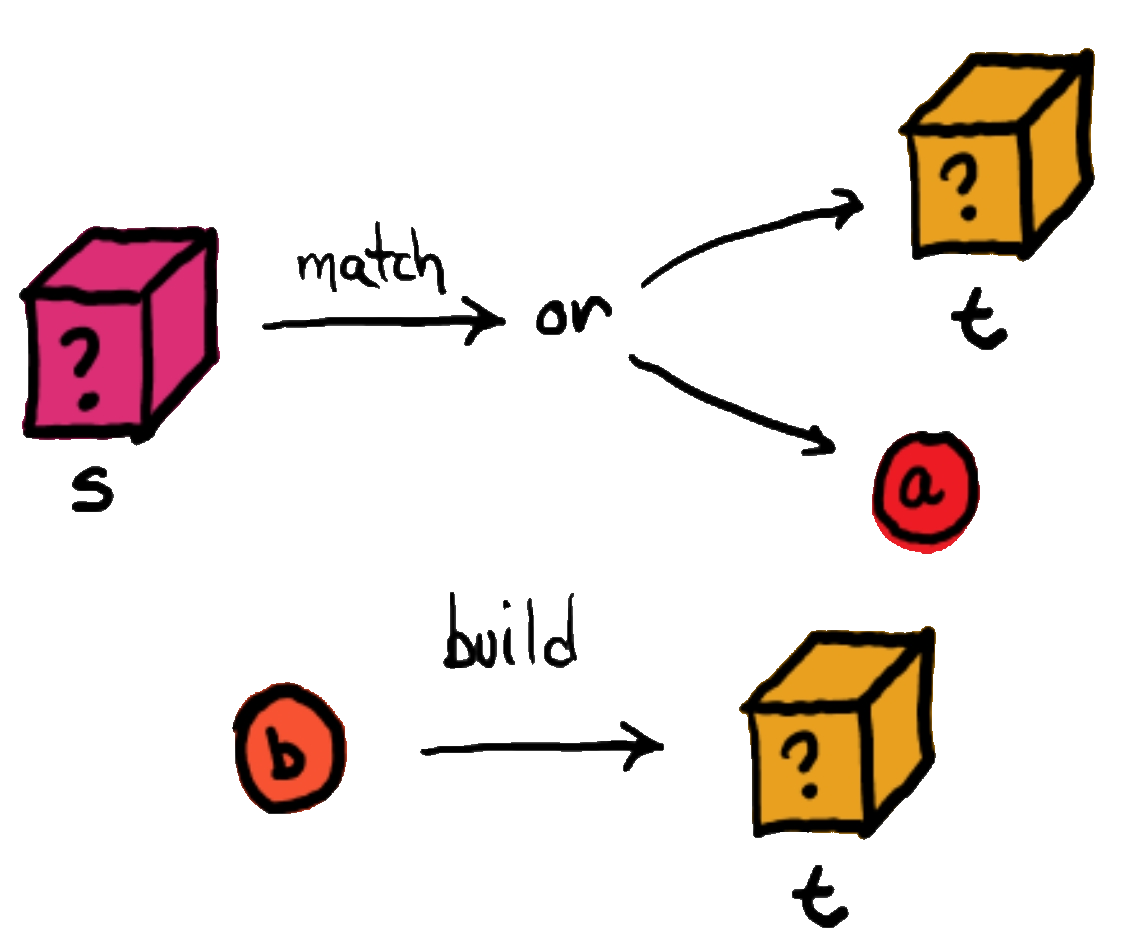

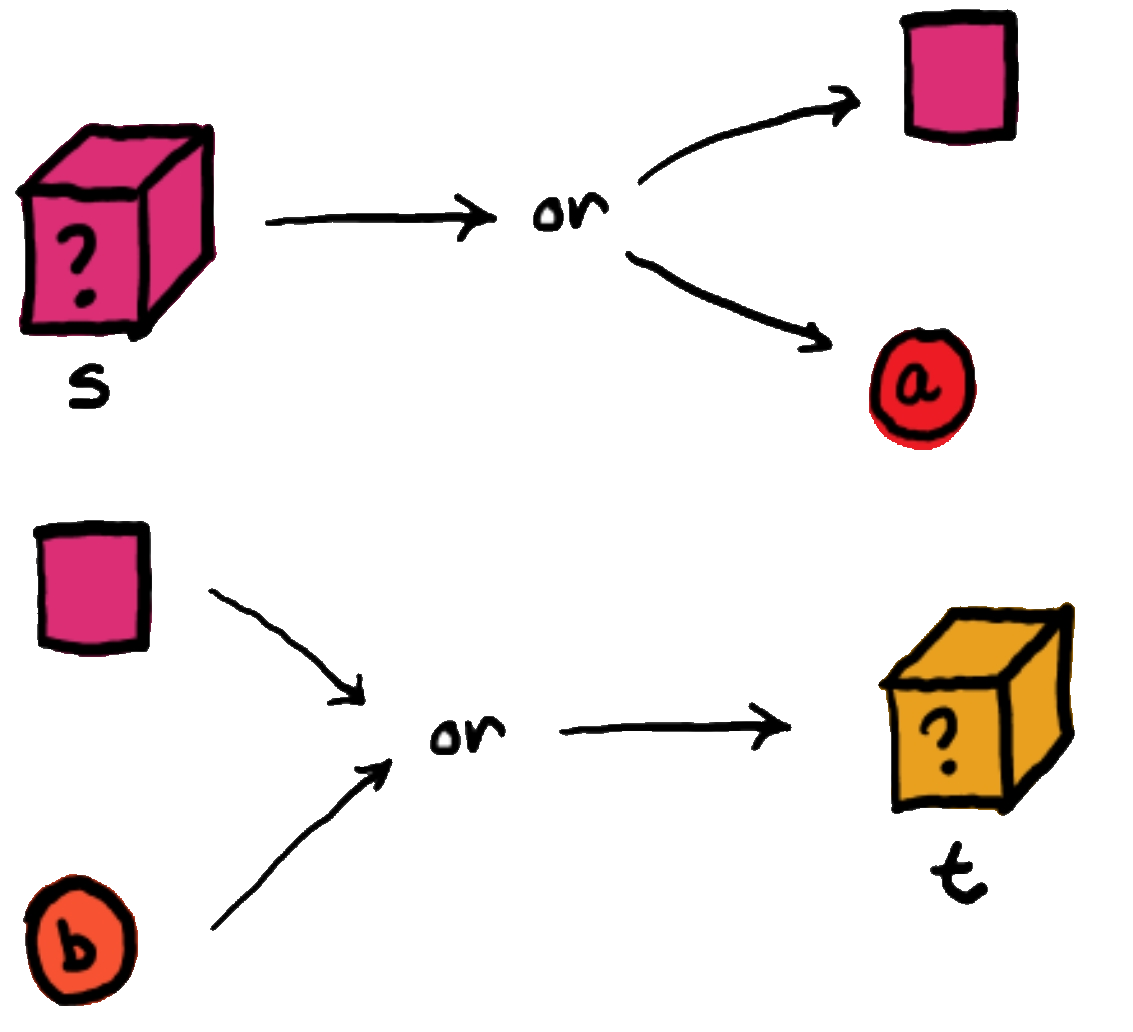

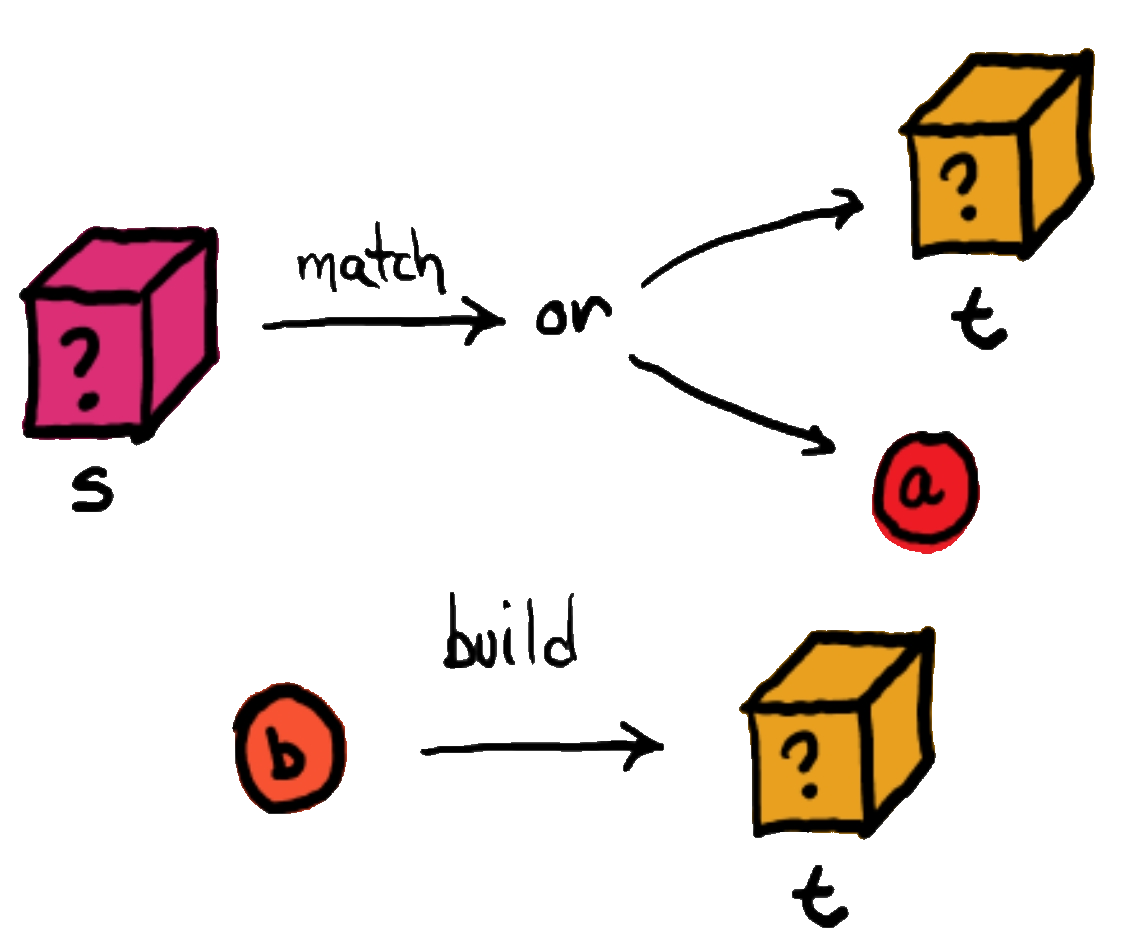

As with product types, there is an optic for viewing and updating with sums, called a prism. In functional programming, a prism between two pairs of types and consists of two functions and . We interpret as the type for the original, possibly more abstract, data structure; is the type of its updated version; is the type of some concrete form can take; and is the type that will replace . The function is called a match function and the is a build function. You can skip the following definition if you note that prisms are precisely lenses in the opposite category.

In a cocartesian category , a prism from a pair of objects to a pair of objects is given by two morphisms: a match representing pattern-matching on , and a build representing the construction of the data structure from one of the alternatives.

Example: suppose we have a data structure representing an abstract address. An address is, alternatively, an email address or a postal address like in the previous example. We can try to extract a postal address from a string, returning an abstract address if it fails to match the shape of a postal address. We have also an inclusion of postal addresses into addresses. This can be encoded as a prism.

In Haskell notation, the example reads as follows.

matchAddress :: String -> Either Address Postal

buildAddress :: Postal -> Address

Traversals

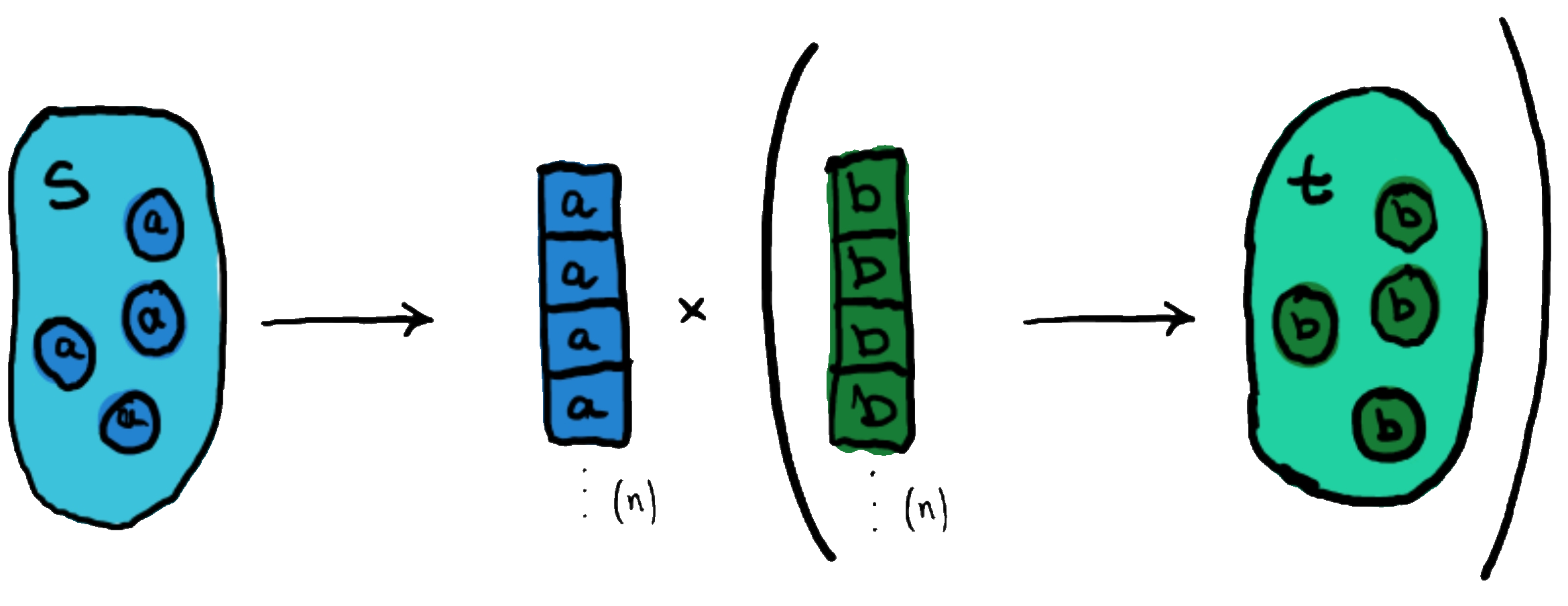

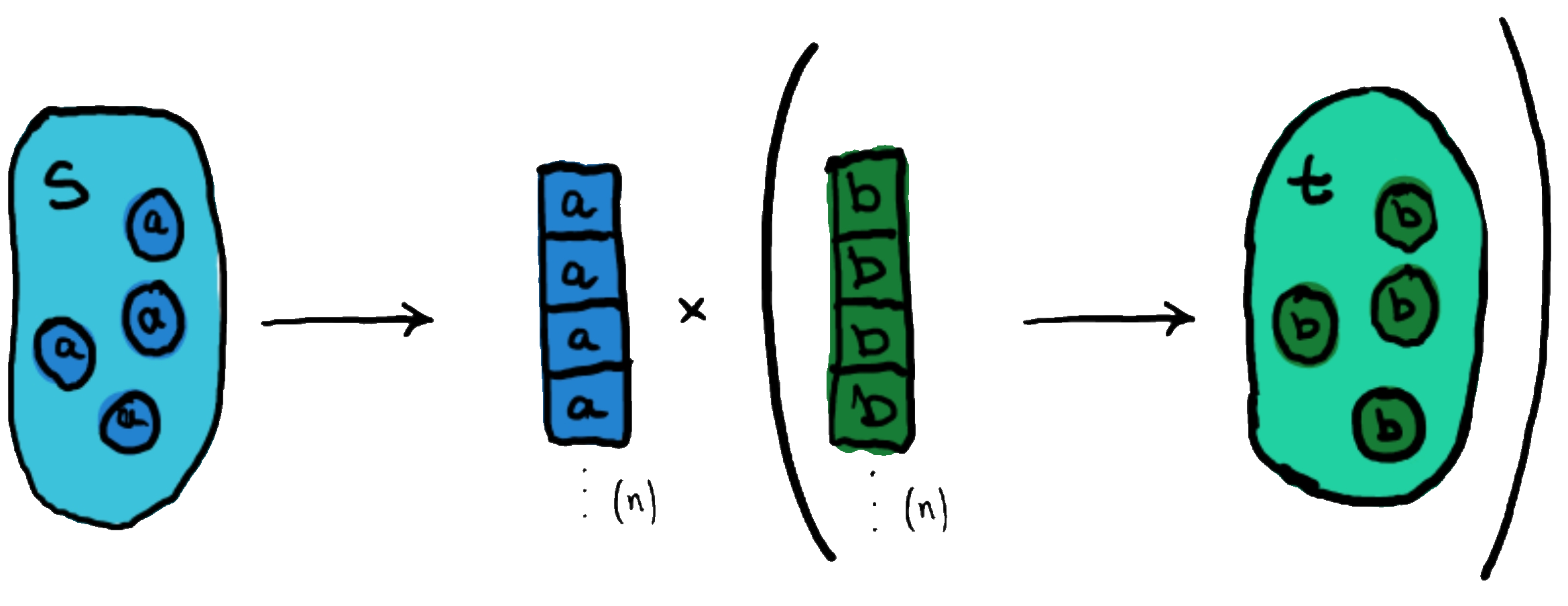

We can go further: optics do not necessarily need to deal with a single focus. Traversals are optics that access a list of foci at the same time. A traversal between two pairs of types and consists of a single function . We again interpret as the original data structure, that is transformed into when we replace a list of elements of type with an equal-length list of elements of type .

In a cartesian closed category with limits and colimits indexed by natural numbers, , a traversal from a pair of sets to is given by a single morphism: an extract that represents extracting a list of some length and a function that takes a list of the same size to create a new structure.

One would think that the traversal can be rewritten in the same style as a lens: that is, as two functions consisting of a get and a put . However, the fact that both must be the same prevents us from writing traversals as a pair of two different functions. This is also what makes a traversal fundamentally different from a lens focusing on a list or tuple type. For the traversal, the length of the output can vary, but we need a list of that same length in each case to be able to update.

Example: suppose we have now a mailing list containing multiple email addresses associated to other data, such as names or subscription options. An accessor for the email addresses is a traversal given by a single function with the following signature:

Note that in Haskell we cannot encode the restriction on length without dependent types.

extract :: MailList -> ([Email], [Email] -> MailList)

The problem of modularity

Writing functions as above is not especially difficult. The problem arises when we want to compose multiple accessors to form a new, valid one. For example, we have an accessor that maybe gets a PostalAddress from a given address, and we also have an accessor that gets the ZipCode of the PostalAddress. How can we get an accessor that maybe gets us the ZipCode directly from any Address if it happens to be a PostalAddress?

-- We have these functions.

getPostal :: Address -> Either Address PostalAddr

setPostal :: PostalAddr -> Address

getZip :: PostalAddr -> ZipCode

setZip :: (PostalAddr, ZipCode) -> PostalAddr

-- And we want the following composition.

getZipFromAddr :: Address -> Either Address ZipCode

setZipAddr :: (Address, ZipCode) -> Address

The naive solution is not particularly difficult to write, but it adds unnecessarily complex boilerplate code that is difficult to maintain. Moreover, the resulting accessor need not be a lens or a prism. Explicitly, in a bicartesian closed category, assume we have a prism given by and , and a lens given by and . We want to compose them into a combined optic from to . The following would be a suitable composition, although it is tedious to write and not particularly illuminating. Here, we call to the product-exponent adjunction (the currying of a morphism).

Note that , and the rest is just a combination of morphisms that uses the product and the coproduct. This approach to composition is not practical: we would need to write down a composition for every pair of optics, and its output could be each time a completely new optic.

This problem is solved using profunctor optics, which we will formally define in the next section. Perhaps surprisingly, some kinds of data accessors have an equivalent formulation in terms of functions that are polymorphic over certain classes of profunctors. For instance, we say that is a cartesian profunctor if it is equipped with a natural transformation such that and , up to the isomorphisms provided by the unitor and distributor of the cartesian product. All the information that goes into a lens can be encoded into an end over a category of cartesian profunctors; that is,

This is convenient because, even if they are equivalent, composition of optics in this representation becomes ordinary function composition.

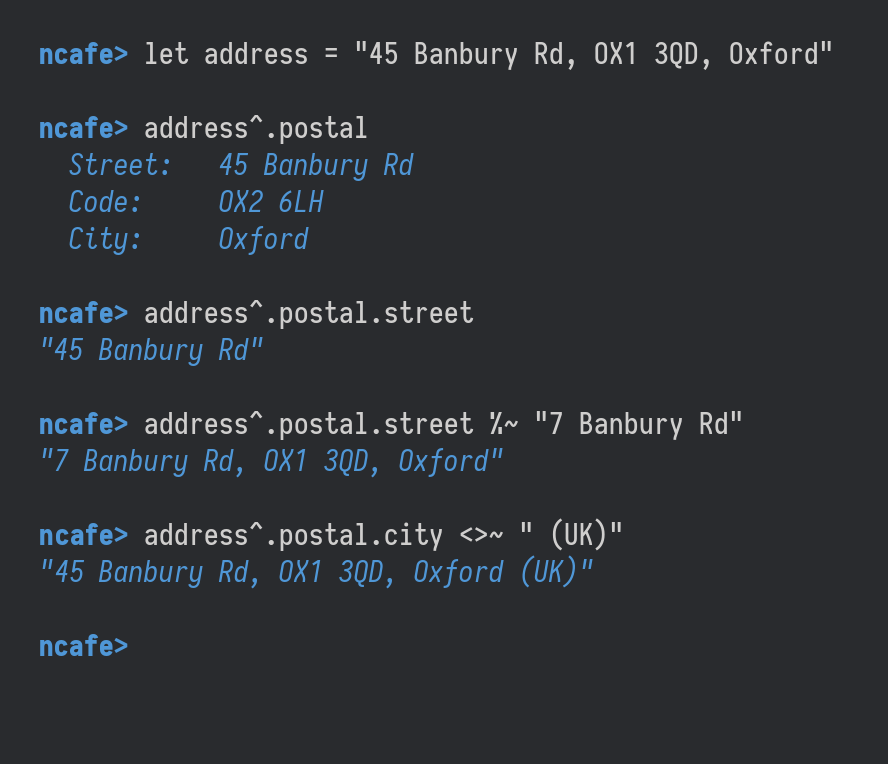

Example

Assume we have already defined the prism as previously shown (matching a string in a postal address) and the lenses that access the subfields of a postal address. In this example,

- we input a string;

- we match it into a postal address using the prism;

- we compose the prism with a lens, using just function composition in Haskell, to access the street inside the address;

- update the street with a new value;

- apply a function to the city part of the postal address.

That is, with this representation, we do not need to worry anymore about boilerplate functions polluting our code. This poses two main questions: first, why and how does this work? and secondly, can we have a unified profunctor representation for some definition of optic?

The existential encoding of optics

A first approximation to the general definition of optic can be found in Milewski’s 2017 post At first, the definition there encompasses only the case where the action is given by (the currying of) a monoidal product ; but towards the end, this is extended to any action given by an inclusion of some subcategory of endofunctors . After this, a definition of optic can be found, with slight differences, both in Boisseau and Gibbons’ “What you needa know about Yoneda: Profunctor Optics and the Yoneda Lemma (Functional Pearl)” and in Riley’s “Categories of optics”.

We say that an action of a monoidal category on an arbitrary category is a strong monoidal functor . In other words, actions are the objects of the slice category ; and we can consider morphisms between them to be commutative triangles there. Considering that monoidal categories are pseudomonoids in , this is to say that these actions are vertical categorifications of the notion of a monoid action. Associated to any action, we can define an optic as follows.

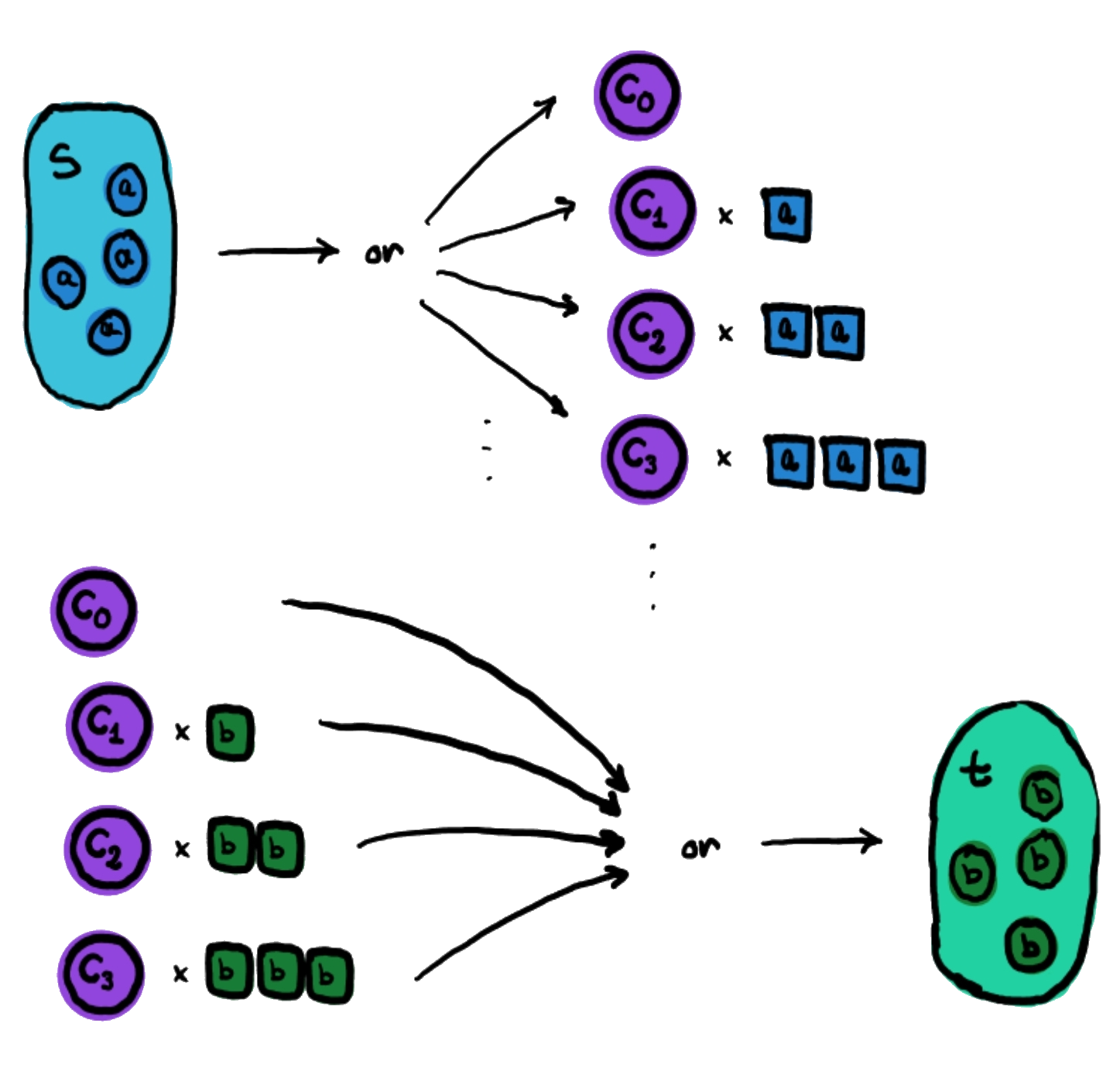

Definition (from Riley, 2018). Let be a strong monoidal functor and let . An optic from to is an element of the following set described as a coend.

An intuition for this definition is that the bigger structure, , can be decomposed into the focus, , and some context, , acting on it. We cannot access the context because of the dinaturality of the coend. However, we can use the context to update the original data structure, replacing the current focus by a new element.

It can be shown directly that can be given the structure of a category, as done by Riley. For our purposes, we will abstain until we reach the section regarding the profunctor representation theorem below so that we can describe as a particular subcategory of a Kleisli category.

Lenses, prisms, grates and traversals are optics

The definition of optic that we have just given actually captures our motivating examples. We will show that the action of the cartesian product gives lenses, the coproduct gives prisms and the action of functors that can be written as a power series gives traversals. In all of these cases, we will be using the Yoneda lemma to integrate over the coend.

Proposition (from Milewski, 2017). Lenses are optics for the cartesian product.

Proposition (from Milewski, 2017). Dually, prisms are optics for the cocartesian coproduct.

The final example from Milewski’s blog post requires an action that is not a monoidal product. In a cartesian closed category , grates from to are defined as follows, where we use for the exponential.

Proposition (from Milewski, 2017). Grates are optics for the action of the exponential .

This was also interesting because grates are a clear example where indexing category, , is not the same as the base category ; and the action is not given by a monoidal product.

Our group’s first goal during this [ACT Adjoint School 2019][act] was to come up with a derivation of the traversal as elementary as possible; and the following is the result of that joint work. Using Yoneda over the category of functors from the discrete category of natural numbers, , we show that traversals are optics for the action that takes any of these functors into the functor given by . Functors of this form are called polynomial functors in a single variable by Gambino and Kock, or L-species. The monoidal product in is given by substitution of polynomials and it can be seen as an instance of Faà di Bruno’s formula. That is, , where with the first sum ranging over all partitions of as a sum of natural numbers.

Proposition. Traversals are optics for this power series action .

We also studied how to directly relate this to the usual encoding of profunctor traversals using traversable functors: these that come with a distributive law for every lax monoidal functor for the product. That derivation was described by Riley relying on a result by Jaskelioff and O’Connor. That discussion is, however, outside the scope of this post.

The profunctor encoding

The profunctor representation of optics is based on a generalization of Tambara modules. The original definition, and the one used by Pastro and Street in Doubles for Monoidal Categories, only concerns monoidal products; but both the definition and the main results can be replicated for arbitrary monoidal actions. Let be a monoidal category and a strong monoidal functor with structure morphisms and .

Definition. A (generalized) Tambara module consists of a profunctor endowed with a family of morphisms natural in both and dinatural on , which additionally satisfy the two equations

In Doubles for Monoidal Categories, Pastro and Street show that Tambara modules are equivalently coalgebras for a comonad defined as

This observation entails that we can consider coalgebra homomorphisms and define the category of Tambara modules, , as the Eilenberg-Moore category for . The comonad precomposes both components with the image of and takes an end; from this description, it can be seen that it has a left adjoint

which must be a monad. More explicitly, the monad acts on a profunctor as

and the adjunction can be computed as follows for any given .

With this in mind, we can go back to the formula for profunctor optics and realize that profunctor optics are exactly optics. The statement of this profunctor representation theorem is the existence of an isomorphism

natural on . The proof is again a sample of coend-fu. This corresponds to the Yoneda with adjunction described in the original blog post.

In fact, we can stop midway there and say that an optic for an action is an element of , which is, again by Yoneda lemma, the same as a natural transformation . That is, we could have defined our category of optics to be the full subcategory of representable functors of the Kleisli category for the monad on the category of profunctors.

We have tried to provide a geodesic path to the proof of the profunctor representation theorem, but the proof proposed in Pastro-Street is slightly different. From that proof, is interesting to remark that we have an identity on objects functor , which is the same as having a promonad, a monoid in the category of endoprofunctors, , whose Kleisli object is . From the universal property of the Kleisli object, it follows that copresheaves over are equivalent to modules over that promonad, and it can be shown that these are precisely Tambara modules.

Profunctor optics

Understanding the profunctor representation theorem solves the mystery of the profunctor encoding. The following equivalences are all corollaries of this theorem.

Lenses are optics for the action of a cartesian category on itself by the product interpreted as . That means that they can be written as functions parametric over Tambara modules for the product. We get our motivating result applying the profunctor representation theorem.

Because of this, the following definition is used in Haskell. Note that profunctors endowed with a Tambara module structure for the product are called cartesian profunctors, or strong profunctors in the lens library.

class Strong p where

strong :: p a b -> p (c,a) (c,b)

type Lens s t a b = forall p. Strong p => p a b -> p s t

Prisms are optics for the coproduct . That means that they can be represented by functions parametric over Tambara modules for the coproduct.

The same applies for them. Note that these Tambara modules were called in Haskell libraries cocartesian profunctors or choice profunctors.

class Choice p where

choice :: p a b -> p (Either c a) (Either c b)

type Prism s t a b = forall p. Choice p => p a b -> p s t

Grates are optics for the action of the exponential . That means that they can be represented by Tambara modules for the exponential.

The implementation in Haskell follows the same idea. Profunctors endowed with a Tambara structure for the exponential are called closed profunctors. In the Discussion section of the blog post, this is called the Related pattern.

class Closed p where

closed :: p a b -> p (c -> a) (c -> b)

type Grate s t a b = forall p. Closed p => p a b -> p s t

Traversables, are optics for the action of polynomial or power series functors and thus they can be represented by Tambara modules for this action.

If we want to use this description, one can implement this in Haskell using sized vectors. However, it is more natural to write it in a language with dependent types such as Idris or Agda. The following is Idris code, where the series is described as a dependent pair consisting on a natural number and the monomial for that number.

series : (Nat -> Type) -> Type -> Type

series c a = (n : Nat ** (c n , Vect n a))

interface Polynomial (p : Type -> Type -> Type) where

polynomial : p a b -> p (series c a) (series c b)

Traversal : Type -> Type -> Type -> Type -> Type

Traversal s t a b = {p : _} -> Polynomial p => (p a b -> p s t)

Composing lenses and prisms

Finally, can we compose optics of different kinds into new optics? In particular, what is the structure we obtain when composing lenses and prisms? The observation is that both lenses and prisms can be seen as particular cases of a different optic: the affine traversal, which has this name because it can be seen as a traversal that has 0 or 1 focus. The composition we discussed at the beginning of the article becomes composition of affine traversals.

Affine traversals

In a bicartesian closed category , an affine traversal over a pair of sets with focus in is defined as a morphism with the following signature.

Affine traversals are optics for an action that takes a pair to the functor . Proving that this is indeed a monoidal action requires associativity to show that . The derivation from the existential is again an application of the Yoneda lemma.

In Haskell, the typechecker infers the most general type at each step. However, it does not check the Tambara structure axioms. When it composes a lens and a prism, it simply joins the Strong and Choice constraints into a new profunctor optic.

Developments and further work

During the ACT Adjoint school we have related the derivation of the traversal we presented to the description using traversables that can be found in Haskell libraries; we have derived some new concrete optics and studied their application in programming contexts and we have sketched a general categorical account of how composition of optics of different kinds works in general (considering both distributive laws and coproducts of monads). We expect to continue working on this, and there are some interesting directions and related work we have not covered here.

We have not considered lawful optics on this post. A general description of how to derive these can be found in Riley’s Categories of optics.

Boisseau and Gibbons’ “What You Needa Know about Yoneda” also describes the approach from functional programming and the description of traversables using traversals.

The basic theory of optics and the coend calculus we use for the derivations work in a similar way for categories enriched over an arbitrary Benabou cosmos. Enriching over the poset , for instance, yields relations instead of profunctors with Tambara modules being relations preserving some structure.

Sometimes the Van Laarhoven representation of optics is used instead of the profunctor representation. Again in Riley’s Categories of optics, the question of when this representation is possible for a given optic is discussed.

Our group would like to thank Jeremy Gibbons, Jules Hedges and David Jaz Myers for helpful discussion on the topic. We would also like to thank the organizers of the ACT school for making this collaboration possible. We thank Bartosz Milewski and Daniel Cicala for reading the drafts of this post and suggesting many corrections and improvements to it.

Re: Profunctor Optics: The Categorical View

Small typo: in the statement of the “profunctor representation theorem” you want . (In the derivation it appears correctly.)