Galois’ Fatal Duel

Posted by John Baez

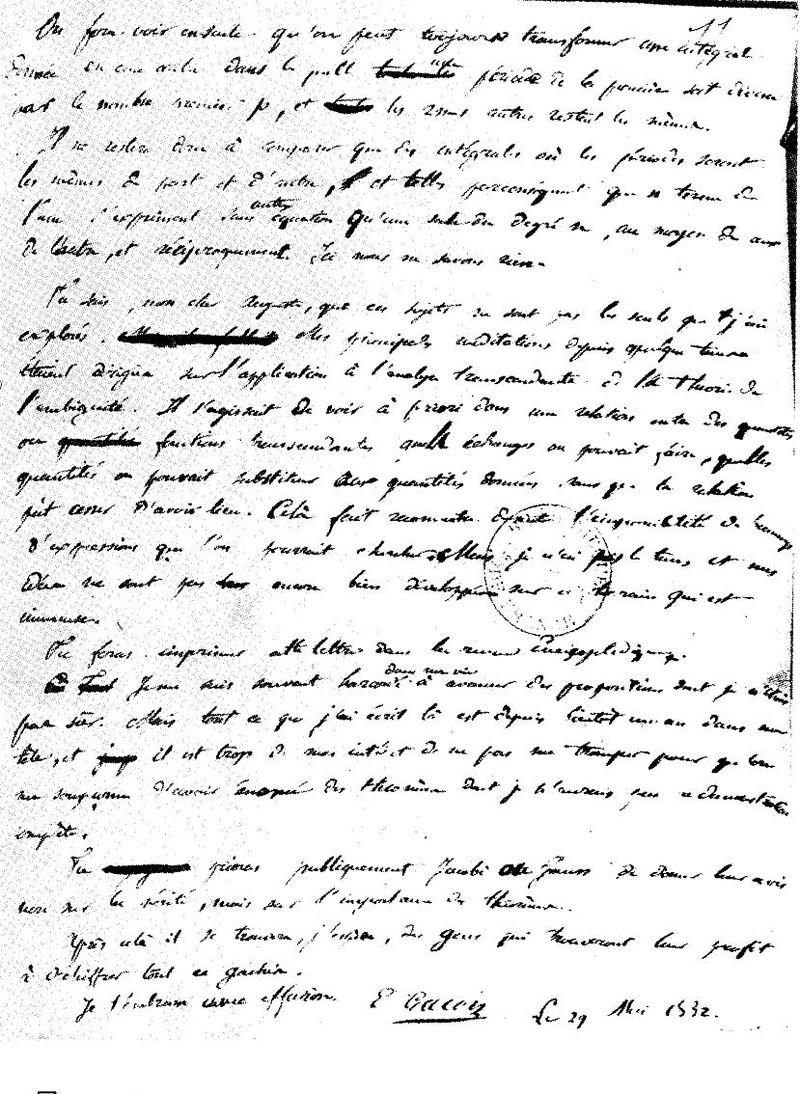

On this day in 1832, Evariste Galois died in a duel. The night before, he summarized his ideas in a letter to his friend Auguste Chevalier. Hermann Weyl later wrote “This letter, if judged by the novelty and profundity of ideas it contains, is perhaps the most substantial piece of writing in the whole literature of mankind.”

That seems exaggerated, but within mathematics it might be true. On top of that, the backstory is really dramatic! I’d never really looked into it, until today. Let me summarize a bit from Wikipedia.

Galois lived during a time of political turmoil in France. In 1830, Charles X staged a coup d’état, touching off the July Revolution. While students at the Polytechnique were making history in the streets, Galois, at the École Normale, was locked in by the school’s director. Galois was incensed and wrote a blistering letter criticizing the director, which he submitted to the Gazette des Écoles, signing the letter with his full name. Although the Gazette’s editor omitted the signature for publication, Galois was expelled.

Galois joined the staunchly Republican artillery unit of the National Guard. He divided his time between math and politics. On 31 December 1830, his artillery unit was disbanded for fear that they might destabilize the government. 19 officers of this unit were arrested and charged with conspiracy to overthrow the government.

In April 1831 these officers were acquitted of all charges. On 9 May 1831, a banquet was held in their honor, with many famous people present, including Alexandre Dumas. The proceedings grew riotous. At some point, Galois stood and proposed a toast in which he said, “To Louis Philippe,” with a dagger above his cup. The Republicans at the banquet interpreted Galois’s toast as a threat against the king’s life and cheered.

The day after that wild banquet, Galois was arrested. He was imprisoned until 15 June 1831, when he had his trial. The jury acquitted him that same day.

All this time, Galois had also been doing math! Earlier, the famous mathematician Poisson had asked Galois to submit a paper to the Academy, which he did on 17 January 1831. Unfortunately, around 4 July 1831, Poisson wrote a reply declaring Galois’s work “incomprehensible” and saying his “argument is neither sufficiently clear nor sufficiently developed to allow us to judge its rigor”. But Poisson ended on a positive note: “We would then suggest that the author should publish the whole of his work in order to form a definitive opinion.”

Galois did not immediately receive this letter. He joined a protest on Bastille Day, 14 July 1831, wearing the uniform of the disbanded artillery and heavily armed with several pistols, a loaded rifle, and a dagger. He was again arrested. During his stay in prison, Galois at one point drank alcohol for the first time at the goading of his fellow inmates. One of these inmates recorded in a letter what Galois said while drunk:

“And I tell you, I will die in a duel on the occasion of some coquette de bas étage. Why? Because she will invite me to avenge her honor which another has compromised. Do you know what I lack, my friend? I can confide it only to you: it is someone whom I can love and love only in spirit. I’ve lost my father and no one has ever replaced him, do you hear me…?”

In his drunken delirium Galois attempted suicide, and would have succeeded if his fellow inmates hadn’t forcibly stopped him.

Remember Poisson’s letter? While Poisson wrote it before Galois’s arrest, it took until October for this letter to reach Galois in prison. When he read it, Galois reacted violently. He decided to give up trying to publish papers through the Academy and instead publish them privately through his friend Auguste Chevalier.

Later he was released from prison. But then he was sentenced to six more months in prison for illegally wearing a uniform. This time he continued to develop his mathematical ideas and organize his papers. He was released on 29 April 1832.

Galois’s fatal duel took place on 30 May. The true motives behind the duel are obscure. There has been much speculation about them. What is known is that, five days before his death, he wrote a letter to Chevalier which clearly alludes to a broken love affair.

Some archival investigation on the original letters suggests that the woman of romantic interest was Stéphanie-Félicie Poterin du Motel, the daughter of the physician at the hostel where Galois stayed during the last months of his life.

Whom did Galois fight in his fatal duel? Alexandre Dumas named Pescheux d’Herbinville, who was actually one of the 19 artillery officers whose acquittal was celebrated at the banquet that led to Galois’s first arrest. On the other hand, newspaper clippings from only a few days after the duel may suggest that Galois’ opponent was Ernest Duchatelet, who was imprisoned with Galois on the same charges. The truth seems to be lost to history.

Whatever the reasons behind his fatal duel, Galois was so convinced of his impending death that he stayed up all night writing letters to his Republican friends and composing what would become his mathematical testament: his famous letter to Auguste Chevalier outlining his ideas, and three attached papers. But the legend of Galois pouring his mathematical thoughts onto paper the night before he died seems to have been exaggerated. The papers were already mostly written.

Early in the morning of 30 May 1832, Galois was shot in the abdomen. He was abandoned by his opponents and his own seconds, and found by a passing farmer. He died the following morning at ten o’clock in the Hôpital Cochin after refusing the offices of a priest. Evariste Galois’s younger brother Alfred was present at his death. His last words to Alfred were:

“Ne pleure pas, Alfred! J’ai besoin de tout mon courage pour mourir à vingt ans!”

(Don’t weep, Alfred! I need all my courage to die at twenty!)

On 2 June, Galois was buried in a common grave in the Montparnasse Cemetery. Its exact location is apparently unknown.

Eleven years later, in 1843, the famous mathematician Liouville reviewed one of Galois’ papers and declared it sound. Talk about slow referee’s reports! It was finally published in 1846.

In this paper, Galois showed that there is no general formula for solving a polynomial equation of degree 5 or more using only familiar functions like roots. But the really important thing is the method he used to show this: group theory, and the application of group theory now called Galois theory.

And for something amazing in his actual letter, read this:

• Bertram Kostant, The graph of the truncated icosahedron and the last letter of Galois, Notices of the AMS 42 (September 1995), 959–968.

Re: Galois’ Fatal Duel

Beautiful and inspiring life story.

There’s a biography by Paul Dupuy.

I wish there were some big budget films on his life. IMDB suggests that there are two titles on his life: The 1965 version and the 2010 version, though I haven’t been able to find them online, the first one seems to be there on YouTube. There’s also this short documentary by Diego Cenetiempo.