The Categorical Origins of Lebesgue Integration, Revisited

Posted by Tom Leinster

I’ve just arXived a new paper: The categorical origins of Lebesgue integration (arXiv:2011.00412). Longtime Café readers may remember that I blogged about this stuff back in 2014, but I’ve only just written it up.

What’s it all about? There are two main theorems, which loosely are as follows:

Theorem A The Banach space has a simple universal property. This leads to a unique characterization of integration.

Theorem B The functor (finite measure spaces) (Banach spaces) has a simple universal property. This leads to a unique characterization of integration on finite measure spaces.

But there’s more! The mist has cleared on some important things since that last post back in 2014. I’ll give you the highlights.

Universal property of Let . The Banach space , with a little bit of extra structure, has a simple universal property.

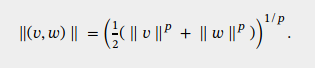

To say what that universal property is, I need to put a norm on the direct sum of two Banach spaces, and the one I’ll use is this:

In words, it’s the power mean of order of the norms of and .

Now consider the category of triples , where is a Banach space, is a point in the closed unit ball of , and is a linear contraction such that . The maps are the linear contractions that preserve the structure in the obvious sense.

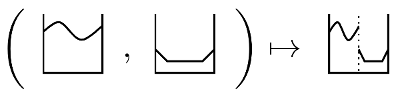

One object of is the triple , where is the constant function and takes two functions on , juxtaposes them, and scales the domain by a factor of :

The theorem is that is, in fact, the initial object of . Among other things, this characterizes the Banach space uniquely up to isometric isomorphism.

When , another object of is the ground field (either or ) together with the element and the arithmetic mean operation . Since is initial in , there’s a unique map . It’s nothing but integration.

Continuous functions on the Cantor set The result I just stated characterized for , but excluded . What about that case?

The category does have an initial object, but it’s not . In fact, it’s , the continuous functions on the Cantor set.

This isn’t as outlandish as it might seem. First of all, the interval and the Cantor set are equivalent as measure spaces. (Here I’m giving the Cantor set the probability measure that corresponds to thinking of its elements as sequences of tosses of a fair coin, and of course I’m giving Lebesgue measure.) So, , which means that the previous result could equally well be thought of as a universal characterization of .

On that basis, one might expect the initial object of to be , the essentially bounded functions on the Cantor set. But it’s not! It’s the continuous functions.

Connecting up with actual function spaces It’s all very well characterizing abstractly, but can we relate its elements to actual functions on ?

The answer is yes, in two different senses.

First, we might want to start with a nice enough function on and produce from it an element of the abstractly-characterized . Let’s interpret “nice enough” as “continuous”, so that we’re looking to derive the inclusion map from the universal properties above.

It can be done! The way it goes is this. The usual map induces a map . Also, the universal property of induces a map from it to . Composing the two gives a map , and I show that in concrete terms, it’s the inclusion.

Second — and in the opposite direction — we might want to start with an element of the abstractly characterized and produce from it an actual function on . Well: we might want to do this, but it’s not realistic: after all, elements of are equivalence classes of integrable functions, up to equality almost everywhere. So that’s the best we can hope to get. There can be no hope of evaluating an element of at an element of .

What the universal property of does get us is a canonical map . Concretely, this is what generations of undergraduates would write as , where . (Thanks to Mark Meckes for pointing this out to me and letting me include it in the paper.)

I’m not saying quite how you get this map ; it’s Proposition 2.4 in the paper. But the point is that this map comes straight from the universal property of , and from we can extract an actual function representing . Indeed, it’s a version of the fundamental theorem of calculus that almost everywhere. So that’s you extract a genuine function.

Conjugate pairing A whole lot of stuff in analysis involves exponents and that are “conjugate”, meaning that . (And a whole lot of people have observed that in retrospect, it might have been better to index the spaces using rather than . Too late!) Most famously, when and are conjugate, and are dual, as long as and are not or .

We don’t seem to get this duality directly from the universal property, but we do get the pairing function

Concretely, this function is . In other words, it’s the composite

where the first map is multiplication and the second is integration. We already derived the second map from the universal property of , and the paper shows how to derive the first map from the universal properties of and .

Sequence spaces Everything so far has been about spaces of functions on . But we can follow a similar strategy to get universal characterizations of spaces of sequences. All I’ll do here is point to Proposition 2.10 of the paper, which states a universal property of the sequence space . That’s for . When you put , what pops out is not but the space of sequences converging to .

The functors The second half of the paper is about as a functor, rather than or .

The construction takes a measure space as input and spits out a Banach space. There are at least a couple of ways in which it’s functorial:

The one you hear about most is that it’s contravariant with respect to measure-preserving maps, via composition.

But it’s also covariant with respect to embeddings (i.e. inclusions of measure subspaces, up to isomorphism). If you’ve got an function defined on a subspace , you can simply extend it by to get an function on all of .

Combining these two types of functoriality, is contravariant with respect to measure-preserving partial maps.

I’ll write for the category of measure spaces and measure-preserving partial maps, so that is a functor

By “measure space” I always mean a finite measure space — not one whose underlying set is necessarily finite, but where the total measure of the space is finite.

For each measure space , there’s a special element of : the function with constant value . The functor , together with the family

has some elementary properties that we could write down. For example, if is a measure-preserving map then maps to .

The second main theorem is that the pair is initial with these simple properties.

That is, I define a category of pairs where and is a family satisfying those elementary properties, and the theorem is that is the initial object of .

Baby versions Actually, this theorem is naturally the third of a trilogy of results. In the paper, I used the first two as stepping stones to get to the third.

The first is about a similar category of pairs , where is now a functor from to the category of mere vector spaces (not Banach spaces). The initial object is the pair , where is the vector space of simple functions on .

The second is about a category of pairs , where is a functor from to the category of normed vector spaces. The initial object is the pair , where is the normed vector spaces of simple functions up to equality almost everywhere, with the -norm.

So, informally:

The universal vector space on a measure space consists of the simple functions.

The universal normed vector space consists of the a.e. equivalence classes of simple functions.

The universal Banach space consists of the a.e. equivalence classes of integrable functions.

Integration on an arbitrary measure space The universal characterization of the functor gives a unique characterization of integration.

Just as for , this comes about by choosing a suitable object of and applying the fact that is initial in . That “suitable object” is the constant functor (the ground field) together with, for each measure space , the total measure . The initiality of gives us a map for each measure space , and it won’t surprise you that it’s our old friend .

The action of functions on measures Whenever you have a measure space and an integrable function on it, you get a new measure on that’s traditionally written as but which I prefer to write as . (It seems to me that the s just make life messier.) It’s defined on measurable sets by

This construction, too, can be derived from the universal property of . This time I won’t say how! It’s not at all hard, but I’m running out of steam, so I’ll just refer you to Proposition 3.10 of the paper. And I’ll note that being able to integrate on arbitrary, “small”, regions of is as close as we can truthfully come to realizing as an actual function, given that in reality is only an equivalence class of functions.

Universal characterization of We all know that there’s something special about , and there’s a theorem that does a little bit to express that special nature. It says that is the initial object of a category of pairs , where is now a functor from to Hilbert spaces. And the axioms that these pairs are required to satisfy are slightly simpler and more intuitive than for general .

What’s the point? I’ve written about as much as I want to for one post, but I didn’t want to finish without mentioning this general question.

A certain kind of no-nonsense mathematician would find all these results very odd. What do they tell us that we didn’t already know? I did a lot of thinking about how to respond, and I gave five answers in the introduction (page 2). I think my favourite one is this:

Fourth, the second main theorem, characterizing the functors, provides a guide for the discovery of new theories of integration. A researcher seeking the right notion of integration in some new context (perhaps some new kind of function on a new kind of space) could follow the same template: decide what kind of spaces the integrable functions should form (perhaps not Banach spaces) and what kind of functoriality should hold, formulate a universal property analogous to the one used below, and find the functor satisfying it.

I leave you to discuss this in the comments!

Re: The Categorical Origins of Lebesgue Integration, Revisited

Looks like a good read, Tom!

We had a small burst of functional analysis meets category theory earlier this year with talk of Smith spaces (aka Waelbrock dual spaces) forming .

Presumably, your universality results could be dualized to Smith spaces.