Counting Points on Elliptic Curves (Part 2)

Posted by John Baez

Last time I explained three ways that good curves can go bad. We start with an equation like

where is a cubic with integer coefficients. This may define a perfectly nice smooth curve over the complex numbers — called an ‘elliptic curve’ — and yet when we look at its solutions in finite fields, the resulting curves over those finite fields may fail to be smooth. And they can do it in three ways.

Let’s look at examples.

The good

In The Riemann Hypothesis (Part 2) we looked at a case of good reduction: an elliptic curve that stays smooth when we work modulo some prime. This curve wasn’t in the standard form I’ve been talking about recently. Instead, it looked like this:

But that’s okay, it’s still an elliptic curve. It turns out to have good reduction at the prime . And this manifests itself when we count points on this curve over the fields where . To count these points we just count solutions of the above equation in and add for the ‘point at infinity’. We get a number I’ll call , where is our elliptic curve:

You can see a lot of patterns here: for example, the number of points is plus a slower-growing correction. We thought about that correction, and ultimately guessed that

In fact this sort of formula is typical for primes of good reduction:

Theorem 1: Hasse’s Theorem on Elliptic Curves. Given a cubic equation with integer coefficients in two variables that defines an elliptic curve with good reduction at , we have

where has .

The Weil Conjectures, now theorems, say how this formula can be vastly generalized. Ultimately this led Grothendieck and others to think about ‘motives’. I said much more about this here. But now let’s move on to the other cases!

The bad: additive reduction

One kind of ‘bad reduction’ happens when our elliptic curve gets a cusp over . To see this pattern it’s easiest to do a cubic curve that’s not even elliptic in the first place. Let’s try this one:

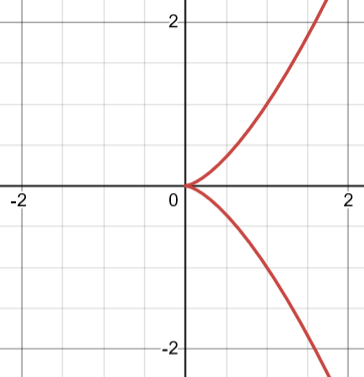

This is not an elliptic curve because it already fails to be smooth over . It has a cusp, visible already in the real solutions:

The cusp is the pointy thing. So we should expect that working over some primes this curve will still have a cusp… and maybe this will affect the count of points in when .

It does! Let’s take the prime again:

You can see the pattern is very different, and it’s much simpler. We just get .

When an elliptic curve has bad reduction at a prime because it gets a cusp, we say it has additive reduction. Here’s what happens then:

Theorem 2. Given a cubic equation with integer coefficients in two variables that defines an elliptic curve with additive reduction at , we have

There’s a reason for this. You’ll notice that is just the number of points in the projective line over . And indeed, it turns out that in this case the curve is just a projective line that’s been mapped into the projective plane in a way that’s one-to-one, but fails to be smooth at the cusp.

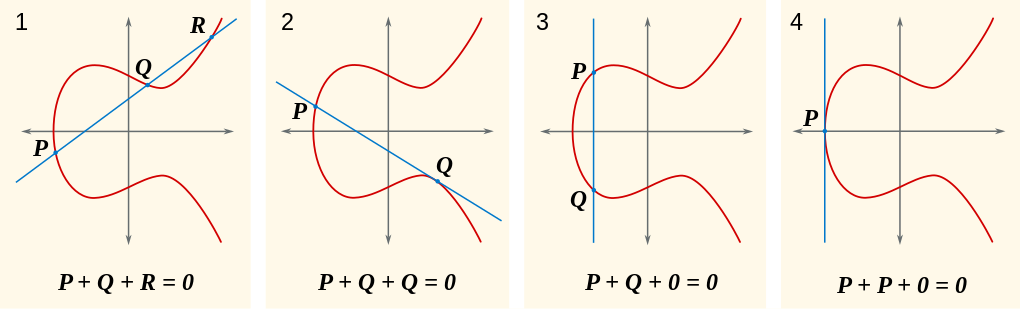

Now what’s with this term ‘additive reduction’? Well, you may have heard that an elliptic curve is an algebraic group. There’s a way to add or subtract points on the curve — a sneaky geometric construction that involves drawing lines between these points:

This still works over finite fields. So in cases of good reduction, is an algebraic group.

All this still works when our curve has a cusp — if you remove the cusp. When you remove the cusp you still get an algebraic group. In particular, the identity of this group is the point at infinity, and we haven’t removed that. And remember, in this case is secretly a projective line except for one non-smooth point at the cusp. So when you remove the cusp you get an ordinary affine line. So it’s not surprising that as an algebraic group, what’s left is isomorphic to the additive group of .

That’s why this case is called ‘additive reduction’.

The ugly: split multiplicative reduction

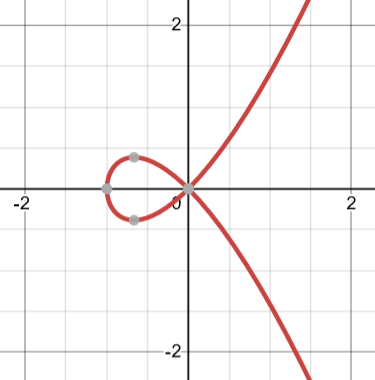

Now for another kind of bad reduction. We say an elliptic curve has multiplicative reduction at the prime if gives a curve that has a node. A node is a point with two different tangent lines — it’s easy to visualize in the real case:

But over a finite field, when you try to compute the slopes of the lines tangent to the node, they may or may not be defined over that field! The reason is that you need to solve some polynomial equations, and finite fields aren’t algebraically complete. If the tangent lines are defined over we say our elliptic curve has split multiplicative reduction, otherwise we say it has nonsplit multiplicative reduction.

Here’s an elliptic curve with split multiplicative reduction over :

I only know this because someone says so — but I know how to check it, and someday I will. For now let’s just count the number of points over when . I have some cheap software that gets really slow when our prime gets as big as , so this table will be pretty small:

Luckily the pattern is obvious! And that’s how this case always works:

Theorem 3. Given a cubic equation with integer coefficients in two variables that defines an elliptic curve with split multiplicative reduction at , we have

Again there’s a reason. Now is one less than the number of points in the projective line over . The reason is that in this case, we get the curve by mapping the projective line into the projective plane in a way that crosses itself at the node. In other words this map is one-to-one except at the node, where it’s two-to-one.

We can can also get an algebraic group out of if we remove the node. When we do that, we’re left with projective line with two points removed — or an affine line with one point removed. So it’s not surprising that as an algebraic group, we get the multiplicative group of , namely

with multiplication as its group operation.

That’s why this case is called ‘multiplicative’.

The weird: nonsplit multiplicative reduction

Here’s a curve with non-split multiplicative reduction at :

And here is the count of points over where :

The pattern is again quite evident, and this case always works this way:

Theorem 4. Given a cubic equation with integer coefficients in two variables that defines an elliptic curve with nonsplit multiplicative reduction at , we have

when is even and

when is odd.

We can play the same game as before and remove the node from . The result is again an algebraic group over . When is even everything works just as in the split case: this algebraic group has points, it’s an affine line with one point removed, and it’s the multiplicative group .

But when is odd things get weird! Now our algebraic group has points. This is just as many points as the projective line over . But there’s no way to make the projective line into an algebraic group! So what are we getting?

Well, we’re getting some weird algebraic group that only exists thanks to the fact that is not algebraically closed!

1-dimensional connected algebraic groups

Indeed there are some theorems that go like this:

Theorem 5. Over an algebraically closed field the only connected 1-dimensional algebraic groups are:

- elliptic curves (which are projective algebraic groups)

- the additive group of (which is an affine algebraic group)

- the multiplicative group (which is an affine algebraic group).

Theorem 6. Over the only connected 1-dimensional algebraic groups are:

- elliptic curves (which are projective algebraic groups)

- the additive group of (which is an affine algebraic group)

- the multiplicative group (which is an affine algebraic group).

- one more connected 1-dimensional affine algebraic group.

Note that all these groups are abelian! The last one, the mysterious one, is what shows up when we study elliptic curves with non-split multiplicative reduction.

For more detail on everything I’ve said, and much more about that mysterious connected 1-dimensional affine algebraic group, go here:

- Alex Youcis, Classifying one-dimensional algebraic groups, Hard Arithmetic.

Reid Barton pointed me to this article. It’s really great, and the only reason for writing mine is that I feel this subject deserves a more elementary introduction.

But before I quit, I want to look at an example of this mysterious connected 1-dimensional affine algebraic group. I want to hold this exotic entity in my hand and gaze at it.

Youcis says it’s the kernel of some homomorphism from the multiplicative group onto the multiplicative group . In other words, it fits into an exact sequence

Let’s do a couple sanity checks. First of all, is a 1-dimensional algebraic group over , while is 2-dimensional. So, just counting dimensions naively, we expect that is 1-dimensonal.

We can also count points: our exact sequence implies

or in other words

so

as we want. And if you’ve ever read my stuff on -arithmetic, this should bring back fond memories.

But what is this group like?

For that, we need to understand the map here a bit better:

The field is a quadratic extension of whose Galois group is . This means there’s some automorphism

of , whose fixed points form the subfield , such that

Youcis claims that is the ‘norm’ of this quadratic extension, namely

All this should remind you a lot of ideas familiar from the real and complex numbers. The group , the kernel of , is analogous to the unit circle in the complex plane since

Let’s look at an example: our friend the prime power , which is actually prime. A cute thing about is that has three elements , and we multiply these just as if they were real numbers! So it’s like a baby version of the real numbers. In other words, there’s an inclusion of multiplicative groups . It’s only when we start adding that things get wonky. Well… actually, adding works as usual, and adding and works as usual too! So the only problem is that now .

The field doesn’t contain a square root of , so we can throw in a square root of and get a quadratic extension. This is a concrete way of thinking about : it consists of guys

where . So it’s like a baby version of the complex numbers. In particular, we can define an automorphism

and then

Thus our desired group , the kernel of , consists of guys with . We know there must be 4, so they must be just the obvious ones:

So is a baby version of the unit circle in the complex plane! And as a group it’s .

Now, we’ve seen that the elliptic curve

has nonsplit multiplicative reduction at . So, Theorem 4 assures us that we can look at the curve it defines over , remove the node from that curve, and get this group .

The equation has four solutions in :

Together with the point at infinity, our curve over has 5 points. When we remove the node at that leaves 4… and I’m claiming these are the points of a connected 1-dimensional algebraic group isomorphic to !

I still haven’t worked out the addition of points in our curve with the node removed, using that well-known but to me somewhat annoying geometrical recipe for adding points on elliptic curves. I should do this and check that this gives a group isomorphic to . But I’m already much happier having looked at this example. The idea of a connected abelian 1-dimensional algebraic group with the same number of points as the projective line really shocked me!

Re: Counting Points on Elliptic Curves (Part 2)

Your theorem 6 is also true over the real numbers! Some might find the theorem there more understandable.